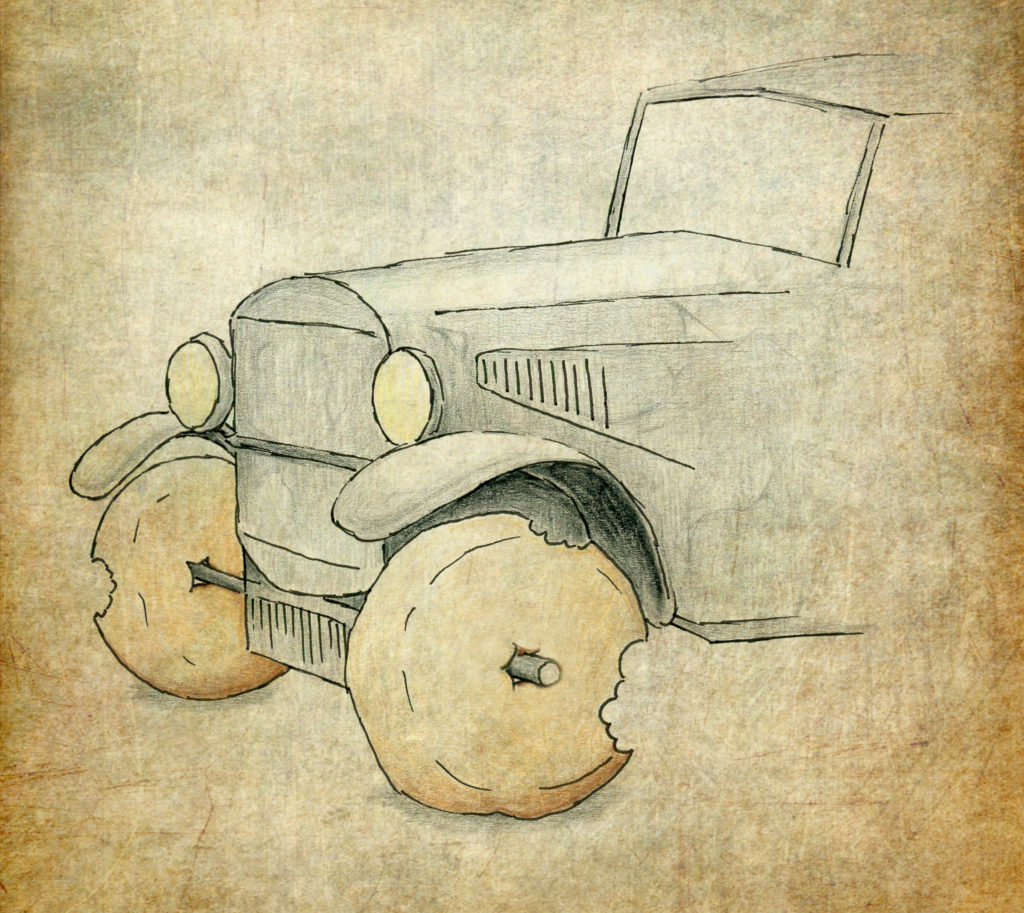

Carolyn Clare Givens is the one who brings you The Warren & the World each week. But as you can see from today’s story, she is capable of far more than the excellent work she does for the SW Newsletter. This charming little story by Miss Givens is accompanied by an equally charming illustration by Mr. Still. Jamin Still is our newest contributor at Story Warren. He’s an artist and an author. In fact, his first picture book (which he wrote and illustrated), is currently available for preorder through Kickstarter. Your family will love it! So after you enjoy this “historical” account of the first car manufacturers, pop over and support Mr. Still’s Ellen and the Winter Wolves. –Sam

—–

Once upon a time there was a man named John Smith. When Mr. Smith was little, he was very concerned that with such a plain name, he would be lost to history, forever forgotten in a sea of John Smiths down through the ages. If you make it to the end of this harrowing tale, you shall discover that young John’s worst fears were realized. Do not worry, though, I haven’t given the whole thing away—there’s still a surprise or two waiting for you just down the page.

When Mr. Smith was a little boy—(How little, you say? Well, littler than me. And probably littler that the eldest among you, but certainly older than the littlest ones.)—Anyway, when John was a boy, he lived on a farm—(Where was the farm? Indiana. But that really doesn’t have any bearing on this story at all. Now hold your questions to the end or we shall never get through this.)

Growing up on a farm was a wonderful thing in those days. It was before the days of motor engines and automation. Farming was long, hard work, but along with it came lots, and LOTS of food. And little Johnny Smith enjoyed food. His mother was considered the best cook in the Three Counties, and her doughnuts were famous in five.

Before he got to eat his mother’s doughnuts for breakfast in the morning though, Johnny Smith had chores to do out in the barn. He’d go out early while it was still dark, and help with the milking and collect the eggs. And if it was a day that his father would need the wagon, John was called upon to pull it out of its space and prepare it to be hitched to the horses.

John liked the days he got to pull out the wagon. He’d check it all around before he started, making sure that all the axles were well oiled and the wheels tight and straight. Then he’d go round to the front and pick up the shaft and pull gently. That was all it took, one gentle pull by a little boy and the wagon would roll forward out of its space, and John could direct it where it needed to go.

The system of axels and wheels always fascinated him. He knew that he shouldn’t be able to pull the wagon by himself, that it was much too heavy for a little boy. But pull it he could—and did—because of how those wheels were put together. Whenever he rode in the wagon, though, Johnny Smith thought nasty thoughts about the wheels. They may have rolled around nicely, but they didn’t ride over rough roads well at all. A ride in the wagon jostled him so much that he always felt afterward he should check his teeth to see they hadn’t cracked.

One morning, after his morning chores—collecting eggs and milking cows and pulling out the wagon—young John Smith sat at breakfast eating his eggs and toast and looking at the pile of doughnuts before him, just waiting to be eaten. As he gazed at the doughnuts, an idea dawned on him. His mother and father and older brother were deep in conversation about something or other, but after a few moments their attention was drawn to John, who had borrowed his father’s knife to create, with his own knife, a chassis and axles. At either end of the knives—the axles—he’d placed a doughnut, and he was rolling the whole contraption back and forth in front of his plate. Of course, it didn’t roll smoothly—John Smith didn’t expect it to, not with flat knives as its axles; that would be silly. No, it wasn’t the axles that concerned him at all—it was the wheels. The gears of his brain were moving, processing his thoughts and ideas—big, fluffy, soft doughnuts. It was genius. He knew it was. And he knew that he had just changed everything.

When John Smith grew up he met a man on a camping trip named Henry Ford. Now I know what you’re thinking. You know about Henry Ford! He’s famous for his assembly line and for making affordable automobiles. But this is a part of Henry Ford’s story you’ve never heard—remember how I told you John Smith would be forgotten by history? Henry Ford is the reason why.

John Smith and Henry Ford got to chatting over the campfire one night and the talk turned to things like motor engines and combustion. Just as it was beginning to get technical, Mr. Smith mentioned that it was always the design of the automobile itself that interested him more than the engine. Mr. Ford caught onto that immediately and began to ask him questions: What did he like about certain designs? What parts of the car were most interesting to him?

Mr. Smith began talking about axles and wheels, and Mr. Ford kept right up with him, nodding along and saying encouraging things like, “Oh, yes, you’re right” and “That’s just it, isn’t it?” And it was all so fortifying that Mr. Smith felt brave enough to mention that idea he’d had all those years ago at the breakfast table with his mother’s silverware and doughnuts.

“The springs and pads of the old wagons and carriages really covered up the jolting caused by those hard wooden wheels rolling along rutted earth,” Mr. Smith said. “But perhaps, just perhaps, the key to a smoother ride could be in the wheels themselves.”

“Oh, yes?” Mr. Ford said. “What do you suggest?”

“Doughnuts,” said Mr. Smith. “Big, giant doughnuts for the wheels.”

Mr. Ford paused, gobsmacked. It took him a moment to recover himself in the light of such brilliance. “Genius,” he said.

So it was that the very first assembly line factory had a bakery attached to it where special bakers fried up huge doughnuts as quick as you like and set them out to cool so that the workers could attach them as the wheels of the Model-D Ford automobile.

Mr. Ford had paid Mr. Smith handsomely for his idea. And Mr. Smith had offered his mother’s doughnut recipe to be used at the factory. Mr. Ford had accepted, and paid another thousand dollars for the rights to the recipe. And after he wrote it out on a card and pocketed his check, Mr. Smith left Detroit and made his way back to Indiana where he lived out his life in peace and quiet, completely unknown.

Why was he unknown, you ask? Well, that’s just the sort of question you should ask—not that silly stuff about how old he was and where the farm was.

You see, Mr. Ford took Mr. Smith’s idea and implemented it, bakery and all, into his assembly line, but the from the very start, he saw that there was a problem with the Model-D. Every single one that came off the line could not pass its final inspection.

Mr. Ford stood there as the very first Model-D bumped its way from the line out to the drive and wondered why it didn’t roll smoothly. He thought he’d turned Mr. Smith’s genius idea into a money maker. But here was the Model-D, bumping along unevenly, jolting and jostling its driver.

Mr. Ford stepped in for a closer look. He looked at the axles, the wheel joints, the shock absorbers. Everything was in perfect order. Then he looked at the wheels. His eyes widened. The wheels had chunks missing from them. Not just any chunks. Mr. Ford could see teeth marks around the edges of the holes.

It was something he’d never foreseen. Something he’d never considered. And something he could do nothing to prevent. Mr. Smith’s mother’s doughnuts were so delicious that the men working the assembly line couldn’t help themselves. In between ratcheting nuts and bolts, they would lean in, sniff the wheels of the Model-D, set their mouths to watering, and just have to take a bite.

Henry Ford had to go back to the drawing board and come up with a new design for the wheels of his automobiles. He shut down the bakery section of the assembly line factory. He talked to various wise people and eventually figured out that he should make the wheels out of rubber. He called them tires and they were the wheel of choice on Mr. Ford’s famous Model-T automobile.

So, now you know why you’ve never heard of John Smith. He lived a happy life, sustained by the money that Mr. Ford paid him fair and square when he thought the doughnuts were a genius solution to the problem of jolting along the road. Mr. Smith’s name was lost to history…but perhaps it is just as well, for had he been remembered, people might have called him foolish for thinking doughnuts would make good wheels for an automobile.

But you and I know better, don’t we? We’ll remember John Smith’s name from this day on as it should be remembered—the name of a boy who looked at a doughnut on the breakfast table and saw, not just good food, but a great round world of possibility.

- The Warren & The World Vol 12, Issue 15 - April 20, 2024

- The Warren & The World Vol 12, Issue 14 - April 13, 2024

- The Warren & The World Vol 12, Issue 13 - April 6, 2024

- Little Orpheus - March 24, 2017

- The Beautiful Place - June 24, 2016

- The Wishes of the Fish King - May 11, 2016

1) “Model-D” = Fantastic

2) This needs to be a picture book.

I LOVED this story. What a creative delight. Well done.

Thanks, Alison! Glad you’ve happened over here–I think you’d love Story Warren. I’ve pointed to some of your recent blog posts in The Warren & the World lately.

*chortle* Well, that was an unexpected treat.

Why does this story sound familiar? Where have I heard this before? Oh, yes…Carrie, my youngest daughter was noodling this idea around my kitchen table! Amazing how ideas generate fun stories.

This is the *best* story ever!!! (And I’m not biased at all 😉

Love this, Carrie! So charming! Also, the word “fortifying” should be used more often.

John Smith… my 2nd great grandfather