For those of us reading blogs such as this one, literacy is a sacred trust. Our children grow up reading or being read to, possibly even before birth. Books are treasures, furniture, pastimes, and art. They are purchased in piles, bestowed with abandon, and brought home from the library in stacks. A world without the written word is inconceivable.

We parents, however, know that books have not always been such a ready commodity. The 15th-century invention of the printing press, which rendered redundant the hunch-backed scribes copying out texts by hand, first brought the cost of books within reach of the middle classes.

But before such technologies could be employed, someone had to land upon the idea of a writing system, or orthography. Imagine being the first to conceive that a person in one place could communicate a complex message to someone out of earshot—or even to an individual living in a later era.

Diverse cultures throughout history have devised various means of employing symbols to represent spoken language. The picture books below are designed to help young people appreciate the wonder that is literacy. Some celebrate the art of orthography itself. Others describe the innovation, imagination, and tenacity of individuals who either devised or decoded ancient writing systems.

Most of us will not, like J.R.R. Tolkien, create detailed languages with grammar and syntax. But these works celebrate the divine design that enables us to communicate complex concepts through language, whether written or spoken.

A glance at the collected titles will reveal that five of the eight books were written (and illustrated) by James Rumford. Languages and writing systems have fascinated this prolific author since childhood. For those of us likewise intrigued with culture, stories, and their constituent components, Rumford’s works offer a varied and informative source of knowledge and fascination.

Liu and the Bird: A Journey in Chinese Calligraphy,

by Catherine Louis and Fen Xiao Min (North-South Books, 2006), 4–8 years, 40 pp.

Author-illustrator Louis tells the story of Liu’s journey over the mountain to see his grandfather. Calligrapher Fen Xiao Min supplies a progression from visual image to Chinese character for sights Liu encounters along the way—crossroads, field, rice, mountain. When Liu arrives at his destination, he recounts his story in pictures.

This simple book introduces readers to the concept of logograms—individual characters that each represent a word. It was originally written in French, making it in a sense tri-lingual.

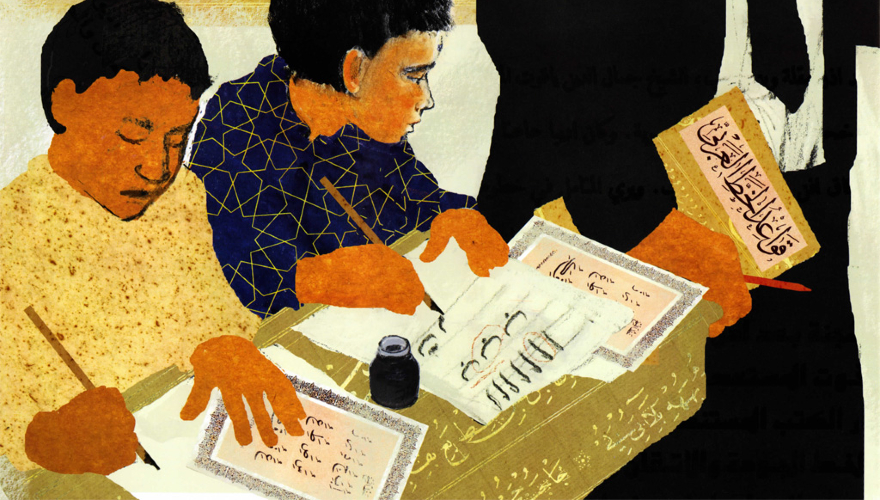

Silent Music: A Story of Baghdad,

by James Rumford (Roaring Books, 2008), 4–8 years, 32 pp.

Silent Music aptly captures the partnership of form and function in written language. It describes an Iraqi boy who loves the shape and flow of Arabic letters and words. This fascination carries him through days and nights filled with the sounds and hazards of war. The text, alongside collage-style art, touches on the artistic legacy of Arabic calligraphy as well the modern history of Iraq.

Sequoyah,

by James Rumford (Houghton Mifflin, 2004), 4–8 years, 32 pp.

I was surprised and a trifle chagrined not to have heard of Sequoyah prior to reading Rumford’s book. This 19th-century Cherokee devised a writing system for his people that remains in use today. At one point literacy among the Cherokee is estimated to have neared one hundred percent. Rumford’s text is conveyed both in English and in Sequoyah’s orthography. The book is an inspiring testimony to the power of one individual’s vision and perseverance.

Bright Star,

by James Rumford (Monoa Press, 2016), 5–8 years, 44 pp.

In the late nineteenth century, a young African king named Njoya found his territory overrun by European colonizers. Situated in what would eventually become Cameroon, Njoya took note of the colonizers’ strengths and adapted them for his people, the Bamum. He created a writing system, established schools, and taught himself architecture in order to design his own palace.

Sadly, French colonialists exiled Njoya in 1931; he died two years later. Although the colonial government banned the Bamum language, it persisted until Cameroon gained its independence in 1960. Bamum is now regarded as an endangered language; at least one project is aimed at its preservation.

There’s a Monster in the Alphabet,

by James Rumford (Houghton Mifflin, 2002), 6–9 years, 40 pp.

Informed by orthographic history, Rumford speculates on the dawn of the Phoenician alphabet. He explains how each Phoenician letter was originally a pictograph. Over time the initial sound of the word came to be assigned to its associated letter. For instance, the pictograph for “monster” might eventually come to represent the sound “m.”

There’s a Monster in the Alphabet represents Rumford’s adaptation of the legend of Cadmus and the founding of the ancient Greek city of Thebes. Rumford weaves the Phoenician alphabet into the story. A graph at the end shows how modern alphabets—Greek, Hebrew, English, and Arabic—reflect their Phoenician origins. The graph also enables readers to decode the Phoenician words embedded in Rumford’s illustrations.

Seeker of Knowledge: The Man Who Deciphered Egyptian Hieroglyphics,

by James Rumford (Houghton Mifflin, 2000), 4–8 years, 32 pp.

This brief account of the life of Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832) effectively captures the excitement of intellectual discovery. Champollion’s dedication, perseverance, study, and even rejection culminated in a breakthrough at age thirty that would enlighten historians for generations to come. Rumford inserts a number of glyphs into the text; marginal insets define and describe others. Back matter includes enticing volumes for older readers on reading and deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Secrets in Stone: All About Maya Hieroglyphs,

by Laurie Coulter, ill. Sarah Jane English (Little Brown Young Readers, 2001), 8–13 years, 48 pp.

This longest and most complex of the books in this list is also my favorite. The history of the discovery and interpreting of the Mayan writing system spans nearly two centuries. The author interweaves her account of this fascinating process with brief accounts of Mayan history and culture. The text introduces numerous archaeologists, artists, linguists, and explorers who contributed to the task of discovery.

One of these, David Stuart, began studying the Mayan artifacts as a teen. In 1983, at age 18, his accomplishments earned him the honor of becoming the youngest recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship. The legacy of these scholars, along with the abundance of interactive suggestions provided in the book’s sidebars, marginal notes, and back matter, could inspire a new generation of linguists and scholars.

The Alphabet Makers,

Museum of the Alphabet, Waxhaw, North Carolina (SIL International, 3rd ed. 2011), 100 pp. This exquisite softcover volume is out of print but available secondhand from various online booksellers. The majority of its content represents a historical overview of written languages worldwide. The accessible text is accompanied by drawings, attractively designed charts, and photographs of ancient documents and artwork. Brief segments at the end describe other orthographies (i.e. for music or the visually impaired), the contributions of modern technology, the process of documenting contemporary unwritten languages, and literacy promotion. Adults as well as teens can enjoy browsing topics of particular interest or reading cover to cover.

- Birthday with the Bard - April 10, 2024

- What History Is Made Of - March 25, 2024

- Books for Black History Month, pt. 2 - February 19, 2024

Oh this is a great list and one I’m definitely going to make use of! Just this last week our five year old decided to start learning the Hebrew alphabet… Thank you.