List-making is practically a hobby with me, and books are a passion, with children’s literature a high-ranking subcategory. Creating lists of the latter is thus a delight accompanied by the danger of disappearing into long, winding passageways papered over by picture books.

This is especially true of a topic as fascinating and fruitful as women’s history. The last few decades have seen an ever growing wealth of picture book biographies of all sorts, produced by innovative authors and gifted illustrators. Many document the lives of women notable for their gifts, passion, and commitment to a cause. In most cases these individuals didn’t set out to make a name for themselves. They had a passion and they pursued it; they perceived a need, and they addressed it. Some were exceptionally gifted; some simply refused to look the other way when confronted with injustice or hardship.

Most of the women featured below overcame adversity of some sort, whether physical, economic, or social. Generally at least one parent supported their goals, but many lost a mother or father in childhood. These women are significant not because of their gender but because they rose above their circumstances.

It’s unlikely I will make great advances in science—or the arts, for that matter. And it’s possible my own greatest adversary is various iterations of my own psyche. But women like Sarah Hale, writer of letters, books, poetry, and more, remind me that the important thing is to keep going and not lose heart. I hope the perseverance of these visionaries will inspire you and your daughters and sons as it has inspired me.

Firsts and Activism

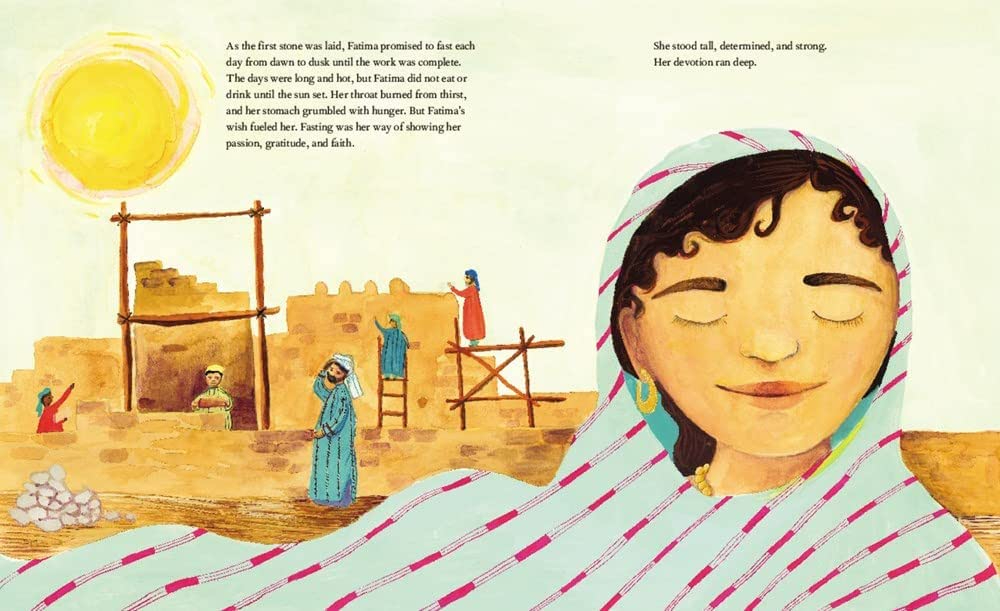

One Wish: Fatima al-Fihri and the World’s Oldest University, by M. O. Yuksel, ill. Mariam Quraishi (Harper, 2022, ages 4–8, 40 pp.) So much about this book thrilled me. The history of the world’s oldest continuously operating university is, in itself, fascinating. Quraishi’s watercolors, particularly her botanicals, are lovely. And learning that the creators hail from parts of the world for which I have particular affinity heightened my already existing enthusiasm for the work. But readers of any background can admire al-Fihri’s one wish to establish a school that would offer education to all, regardless of social or economic status.

Nurse, Soldier, Spy: The Story of Sarah Edmonds, a Civil War Hero, by Marissa Moss, ill. John Hendrix (Abrams Books, 2011, ages 6–9, 48 pp.) Moss’s engaging storytelling and Hendrix’s lively drawings do justice to Edmonds’ colorful life. This courageous, determined woman took on a male persona and fled to Canada three years before the Civil War in order to escape an arranged marriage. Her exploits during and after the war impress and inspire. She refused medical treatment when injured for fear of being found out as a woman; worked behind Confederate lines in the guise of a freed slave in order to gather intelligence; and, after the war, worked on behalf of African Americans and veterans.

Thank You, Sarah: The Woman Who Saved Thanksgiving, by Laurie Halse Anderson, ill. Matt Faulkner (Simon & Schuster, 2002, ages 5–10, 40 pp.) Sarah Hale’s status as America’s first female magazine editor was enough to designated her a hero in my book. But even more importantly than this historic first, Hale used her influence to campaign for social change: abolition, schools for girls, playgrounds, women’s clothing reform—little escaped her active pen. Quirky text and illustrations relate how this tenacious woman lobbied five different presidents over a period of thirty-eight years for a national thanksgiving holiday. At last, in 1863, Abraham Lincoln saw eye to eye with the feisty, implacable activist. Anderson’s four pages of back matter aim for an objective account of the sometimes fraught history of this holiday, a snapshot of 1863 social conditions and historic events, and a more complete biography. * See also, Sarah Gives Thanks,by Mike Allegra, ill. David Gardner (Albert Whitman, 2012)

Fly High: The Story of Bessie Coleman, by Louise Borden and Mary Kay Kroeger, ill. Teresa Flavin (Margaret K. McElderry Books, ages 9–12, 40 pp.) In 1921 Coleman became the first African American to obtain a pilot’s license. Fly High portrays the young woman’s perseverance and determination as she studies, works, and saves to train as a pilot in France. Borden draws attention to the faith of Coleman’s mother, as well as Coleman’s own, and her influence on thousands of her contemporaries. Absorbing text and animated illustrations effectively capture the historical and social context of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Amelia and Eleanor go for a Ride, by Pam Muñoz Ryan, ill. Brian Selznik (Scholastic, 1999, ages 7–10, 40 pp.) That Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean in 1932, a decade after Coleman obtained her pilot’s license, is common knowledge. Less well known is her friendship with first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Ryan’s dazzling descriptions and Selznik’s two-tone photo-realistic illustrations depict the camaraderie of these two spirited women and their escapades one April night in 1933. Back matter explains Ryan’s flights of creative license, but the facts are inspired by true events.

Politics and Government

I Could Do That!: Esther Morris Gets Women the Vote, by Linda Arms White, ill. Nancy Carpenter (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2005, ages 7–9, 40 pp.) Esther Morris makes me want to cheer. She attended abolitionist meetings at the first anti-slavery church in the North, campaigned for women’s suffrage, and stepped up to do the much-needed work of tending, nursing, and nurturing in her wild West town. When the women of Wyoming became the first in the nation to get the vote, they had Esther Morris in large part to thank. And when the local justice of the peace resigned in protest, none other than Morris took his place, becoming the first woman in the country to hold public office. The life of this milliner-cum-judge proves you don’t have to be a big name to make a big difference. Carpenter’s humorous illustrations aptly accompany White’s sprightly account, punctuated by Morris’s spunky refrain: “I could do that!”

The Only Woman in the Photo: Frances Perkins and Her New Deal for America, by Kathleen Krull, ill. Alexandra Bye (Atheneum, 2020, ages 4–10, 48 pp.) I’ve heard and learned about Roosevelt’s New Deal in school, from my mother-in-law who lived through it, from my father whose father worked in a CCC camp, and elsewhere. But no one mentioned that Roosevelt’s secretary of labor, closely involved in designing and drafting many of his policies, was a woman.

Frances Perkins went from being a painfully shy girl to one of the early social workers, the first female member of a presidential cabinet, and the longest-standing secretary of labor in U.S. history—twelve years. Her legacy is hidden in large part because she continued to shrink from publicity and acclaim throughout her life. She was driven by concern for justice and the conviction that all members of society—including the young, the elderly, and the disadvantaged—deserved the right to fair wages, safe working conditions, and access to basic necessities.

A Life of Service: The Story of Senator Tammy Duckworth, by Christina Soontornvat, ill. Dow Phumiruk (Candlewick, 2022, ages 5–9, 48 pp.) Regardless of one’s politics, the persistence Tammy Duckworth has demonstrated in overcoming hardship to serve her country is laudable. In her early years Duckworth’s family was on diplomatic duty in SE Asia. When her father lost his job, they settled in Hawaii, where they teetered on the verge of homelessness. Nevertheless, Duckworth excelled in school. She signed up for ROTC in college, inspired by the camaraderie and discipline shared by her fellow recruits. After being shot down in the Iraq War, now an amputee, she was persuaded to run for public office. As a representative and senator she has continued to advocate on behalf of refugees, women, families, veterans, and the disabled.

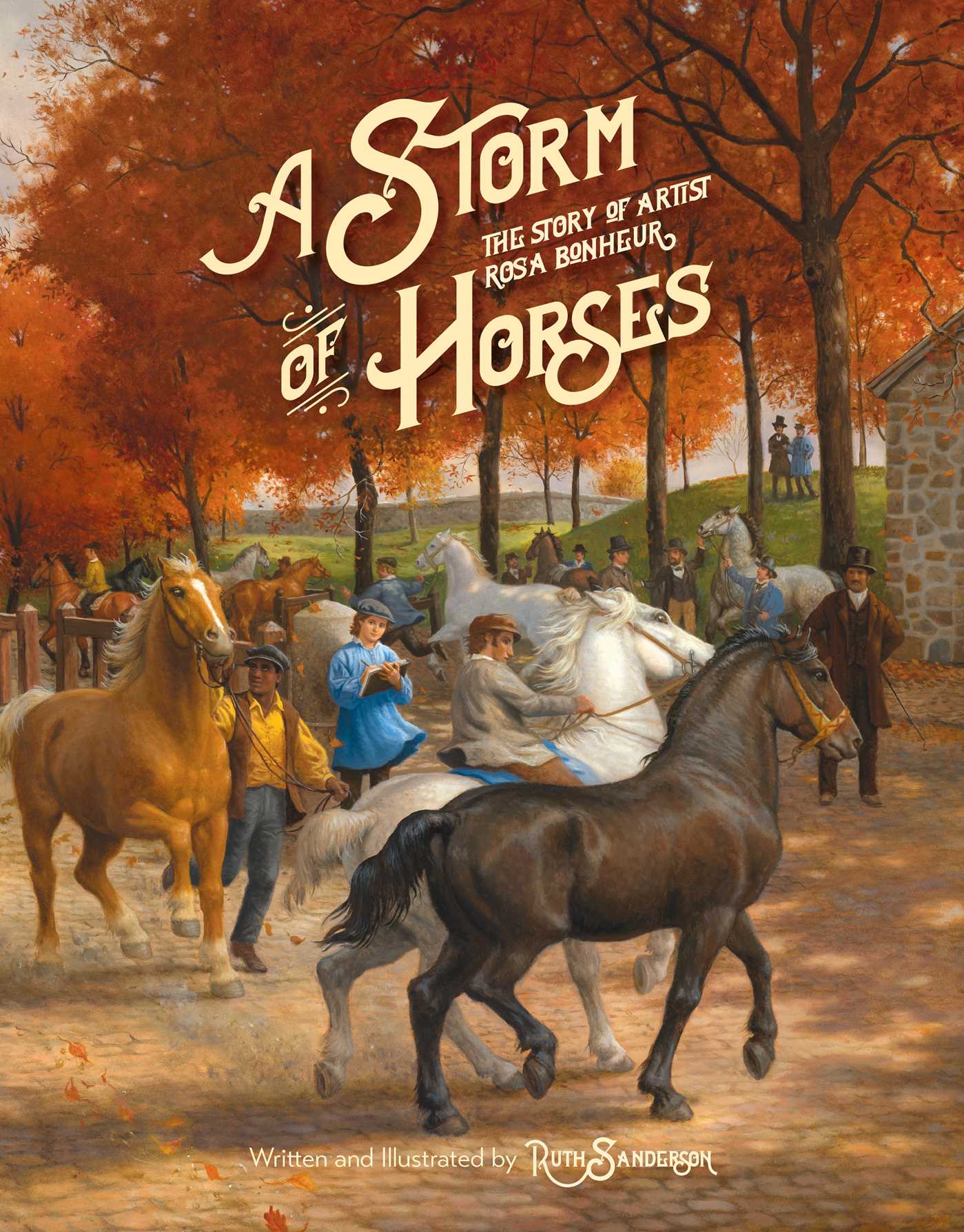

Arts

A Storm of Horses: the Story of Artist Rosa Bonheur, by Ruth Sanderson (Crocodile Books, 2022, ages 6–12, 40 pp.) In childhood Bonheur was encouraged by her painter father to develop her love for capturing on canvas the power and beauty of living creatures. With this opportunity, a rarity for nineteenth-century women, she became one of the foremost animaliers of the nineteenth century. Sanderson’s double-spread, full-page illustrations honor Bonheur’s lush, realistic style and document her development, painting process, and success. An extended five-page biography in the back fills in the gaps. Included are lists of recommended drawing books and sites where Bonheur’s art can be viewed in person.

Trailblazer: the Story of Ballerina Raven Wilkinson, by Leda Schubert, ill. Theodore Taylor III (Little Bee Books, 2018, ages 6–9, 40 pp.) As one of the first African-American ballerinas to dance with a major U.S. company, Wilkinson repeatedly faced rejection and racial prejudice. Schubert depicts Wilkinson, a devout Catholic, responding with not only resolve but grace. Schubert’s narrative is bookended by letters to the reader from ballerina Misty Copeland and Wilkinson herself. The latter’s generosity of spirit comes through in her statement that, “this is a story about all of us and the hope that lights our way.”

Bunheads, by Misty Copeland, ill. Setor Fiadzigbey (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2020, ages 4–10, 32 pp.) This charming story introduces readers to a young Copeland, the first African-American female principal to dance with the American Ballet Theater. It depicts a budding friendship between the gifted Copeland and her talented new friend, culminating with their shared triumph. Well suited to younger readers, Bunheads showcases the delight of dance and the joys of collaboration.

The World is Not a Rectangle: A Portrait of Architect Zaha Hadid, by Jeanette Winter, (Beach Lane Books, 2017, ages 3–8, 56 pp.) Combining simple illustrations with sparse but lyrical text, Winter conveys Hadid’s innovative vision to young readers. The Iraqi-British architect was committed to representing the shapes and lines of nature in architecture. Despite skeptics who declared her designs unbuildable, they at last found acceptance. Hadid became the first female recipient of various international awards and the first woman to design a museum in the United States.

Science

Dinosaur Lady: The Daring Discoveries of Mary Anning, the First Paleontologist, by Linda Skeers, ill. Marta Álvarez Miguéns (Sourcebooks, 2020, ages 4–8, 40 pp.) Colorful illustrations and lively text sprinkled with Latin names of dinosaurs appeal to a range of ages. Though I had read about Anning before, I marveled again at the discoveries unearthed by this self-taught scholar of natural history. Born in 1799, she was barred from scientific societies as a woman. But in 2010 the Royal Society of London designated her “one of the ten most influential woman of science.” * For slightly older children, see Stone Girl, Bone Girl, Laurence Anholt, ill. Sheila Moxley(Francis Lincoln, 2006).For a description of Mary’s first dinosaur discovery, alongside classically realistic oil paintings, see Mary Anning and the Sea Dragon, Jeannine Atkins, ill. Michael Dooling(Farrar Strauss, 2012).

Marie Curie, by Demi (Henry Holt, 2018, ages 4–8, 40 pp.) Not being particularly scientifically inclined, I knew only the barest outline of Curie’s accomplishments. Though elementary in its presentation, Demi’s fascinating narrative expanded my knowledge by orders of hundreds. I had no conception of the home laboratory in which Mme. Curie and her husband carried out their experiments. And I was unaware that not only did the two discover radium and polonium; they posited, based on their own uncomfortable exposure to these radioactive elements, their uses in eliminating cancerous tissue. I learned the Curies’ daughter, Irene, went on to become a chemist and, like her mother, receive a Nobel Prize alongside her husband.

Demi is forthcoming about the damage caused by widespread use of radioactive elements before their dangers were fully understood. The Curies themselves suffered from extended exposure, although Pierre died in a tragic accident before symptoms could manifest fully. On her own, Mme. Curie accrued a host of accolades. But she did more than secure her place in history; she served humanity both through scientific advancement and practical service. During WWII, the fleet of mobile X-ray units she commissioned to treat soldiers came to be known as “Little Curies.”

Maria’s Comet, by Deborah Hopkinson, ill. Deborah Lanino (Aladdin, 2003, ages 3–8, 32 pp.) This book was my first introduction to Maria Mitchell; I read it over and over with my daughter, starting when she was a preschooler. It still stands out, partly due to nostalgia, and partly because of Hopkinson’s use of lyrical language and delightful imagery. Added to that, Hopkinson is a fellow Oregonian and among my all-time favorite writers for children. Simple but elegant text and lovely illustrations make it perfect for introducing youngsters to an accomplished woman who was herself a teacher and mentor.

What Miss Mitchell Saw, by Hayley Barrett, ill. Diana Sudyka (Beach Lane Books, 2019, ages 4–8, 40 pp.) Heavenly objects and starry-eyed girls clearly give rise to beautiful books. Barrett and Sudyka, too, have partnered on an enchanted comingling of word and image. Barrett portrays Mitchell learning names, from those of ships to shopkeepers, in childhood, moving on to the names of stars and celestial phenomena in adolescence. Ultimately Mitchell’s own name becomes attached to the comet she sighted. As promised, the King of Denmark sends her a gold medal inscribed with the name—Maria Mitchell—still associated with scientific achievement.

Barrett includes the Vatican astronomer whose claim to the comet rivaled Maria’s, as well as the response from the international scientific community. Two pages of back matter fill in details of Mitchell’s life and the influence of her Quaker upbringing. *For creative, collage-style illustrations and consideration of qualities contributing to success—both in Mitchell and in readers—see The Astronomer Who Questioned Everything,by Laura Alary, ill. Ellen Rooney (Kids Can Press, 2022).

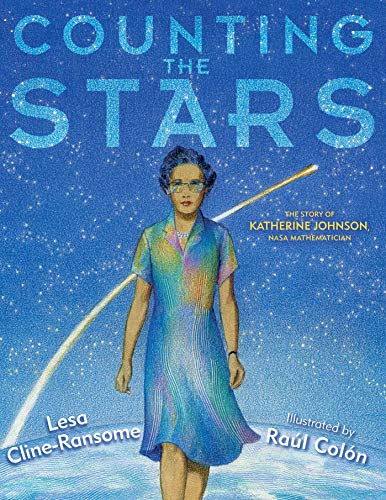

Counting the Stars: The Story of Katherine Johnsons, NASA Mathematician, by Lesa Cline-Ransome, ill. Raúl Colón (Dreamscape, 2019, ages 4–8, 32 pp.) The 2016 movie Hiddden Figures brought attention to Katherine Johnson and other women who broke race and color barriers at NASA in the mid-twentieth century. Today the prospect of working out lengthy, complex calculations by hand, without the aid of computers, is mind boggling. But Johnson’s aptitude for mathematics and accelerated learning (she started high school at age 10) propelled her onto teams of engineers working on the spacecraft that would send the first astronauts into space.

- Birthday with the Bard - April 10, 2024

- What History Is Made Of - March 25, 2024

- Books for Black History Month, pt. 2 - February 19, 2024

Leave a Reply