Layered meanings in children’s literature are nothing new. We’ve all returned to a favorite childhood book and discovered a cache of truths we didn’t perceive the first time around. Ring-Around-the-Rosy, Humpty Dumpty, and other Mother Goose rhymes are purported to signify facts of medieval socio-economics. And even Jesus’ parables, though delivered to a mixed audience, were simple enough for children to understand.

Like utility line markers spray painted on pavement, the familiar scenes of Jesus’ parables pointed to unseen realities lying under the surface of everyday life. The ability to interpret subtle themes enhances the joy of reading. But the opportunity to experience abundant life depends upon reading the signs the Author has embedded in the fabric of Creation, as well as in his written Word.

Children don’t have to grasp themes and symbolism to enjoy quality literature. Preschoolers certainly don’t need to hear that the ring around the rosy is in fact a deadly plague. But engaging illustrations in children’s books can help youngsters develop their own powers of interpretation. Without even realizing it, they learn experientially that literature—as well as life—can operate on multiple levels.

In Something from Nothing (1992), author-illustrator Phoebe Gilman uses pictures not only to enhance the text but to introduce a secondary story—literally underneath the primary story, as it happens—and told entirely without words.

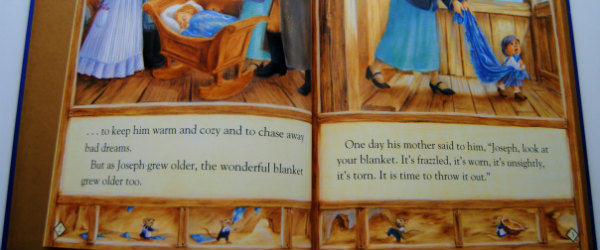

In Gilman’s reimagining of a Yiddish folk song, Grandfather makes a blanket for baby Joseph. By the time Joseph has become a toddler, his mother decides that the blanket has outlasted its usefulness. Grandfather saves it from the dustbin by declaring, after close inspection, that “There’s just enough material here to make … a wonderful jacket.” The jacket becomes, by turns, a vest, a tie, a handkerchief, and a button. Finally, when the button is lost, Joseph turns the whole into “a wonderful story.”

Grandfather exercises his endless ingenuity on the ground floor of a compact cottage in Eastern Europe—where the song originated—while villagers carry on daily life outside. Meanwhile, beneath the floorboards, a family of mice takes up residence and furnishes their home with the scraps from Grandfather’s tailoring. The worn out bits of Joseph’s erstwhile blanket become dresses, overalls, hats, scarves, vests, curtains, tablecloth, bedspreads, a rug, a dinosaur costume (because even baby mice need to exercise imagination), and more. Nor do the mice confine themselves to housekeeping. They go on a picnic, swim in the river, attend Hebrew school, pay visits to friends, and—of course—write and tell stories.

Gilman’s detailed illustrations reward nearly endless perusal. Potential discussion points include village life (street vendors, handmade shoes, laundry in the river), Jewish culture (Sabbath dinner, Hebrew school, traditional food and clothing), Joseph’s progress from babyhood to schoolboy to writer of stories, connections between the activity going on above and below the floorboards, not to mention the values of thriftiness and ingenuity. The crowning truth of the song is the value of story and the fact that we all possess the raw materials: a little life experience and creativity, like that which Joseph inherits from his grandfather.

Gilman’s text adds to the story’s charm and echoes the cadences of folksong. Each time Joseph’s mother describes—in rhyme—the shortcomings of the jacket’s present incarnation, she concludes, “It is time to throw it out.” And each time, Joseph rejoins with absolute confidence, “Grandpa can fix it”; upon which Grandfather turns the article “round and round” and his scissors go “snip, snip, snip,” and his needle flies “in and out and in and out.”

This song has proved a particularly fertile source for creative interpretations. The bright illustrations in Simms Taback’s Joseph Had a Little Overcoat (1999) incorporate animated villagers and animals and utilize cut-outs on each page to represent Joseph’s gradually shrinking garment. In My Grandfather’s Coat (2014), written by Jim Aylesworth, illustrator Barbara McClintock depicts a Jewish tailor’s journey through life, beginning with immigration to America, on to marriage, parenthood, vocational and recreational pursuits, and grandparenthood. A mouse uses up the final threads of the original overcoat, and the story concludes with a mother reading the story to Joseph’s great-grandson, suggesting that while grandfather is gone, his story lives on.

Children think in concrete terms; it’s an important developmental step we don’t want to skip. But while it may be a long stretch from preschool to literary criticism, from picture book to parable is not so far. Illustrations that engage the imagination nudge youngsters toward an appreciation for nuanced literature. But developing skills of interpretation can also help them develop eyes to see and ears to hear the ultimate Story that underlies the visible surface of the material world.

- Birthday with the Bard - April 10, 2024

- What History Is Made Of - March 25, 2024

- Books for Black History Month, pt. 2 - February 19, 2024

Leave a Reply