Recently our family took a field trip to the Museum of Fine Art in Boston. COVID restrictions kept us away for over two years, and as we wandered through the hushed galleries I wondered if my kids would remember anything from our previous visits. Predictably, their memory of the 18th century American furniture proved spotty. The only artifact they recalled from the Egyptian exhibit was a statue of a pharoah, which they remembered not for its grandeur, but because an unsuspecting stranger made a spooky noise that convinced them a spirit lurked within the stone. In other words, they recalled little.

Except Marie.

My daughter, who is six, insisted upon seeing “Marie,” Edgar Degas’ sculpture of “The Little Dancer.” Her excitement so abounded that when we found the right gallery she burst into a run, prompting me to blush and a curator to raise his eyebrows in warning. She circled the statue in awe three times, then attempted to recreate the pose herself. Although her stance hinted more of a kung fu master than a ballerina, the glint in her eyes was priceless. Her mind crackled with delight at seeing the real Marie, the girl she’d read about in Degas and the Little Dancer, who’d inspired the cranky artist to create even when his eyes failed him.

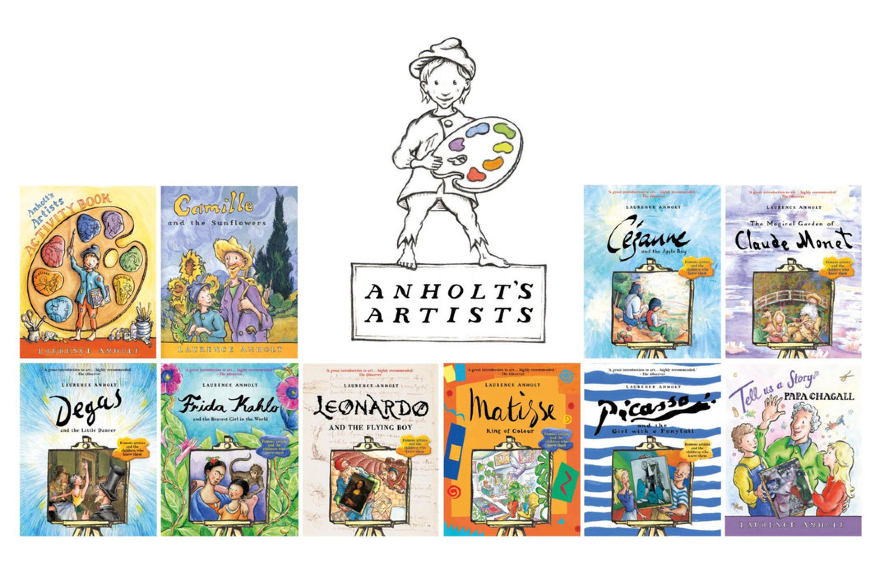

UK-based author and artist Laurence Anholt first wrote and illustrated his artists storybooks over thirty years ago. Each book focuses on a master painter, and Anholt’s own gifts as an illustrator lend a lushness and dream-like quality to the scenes guaranteed to allure young minds. He incorporates the artists’ most famous works into the pages, with characters drifting across Monet’s lily ponds, gazing up into The Starry Night while Van Gogh paints by candlelight, and journeying with Cezanne through the color-block mountains that frequent his paintings. This imaginative approach, seamlessly interweaving art and story, brings some of the world’s most exquisite artwork to life for young readers, with the brushstrokes lingering in their minds long after the story ends.

The true magic of these storybooks, however, is in Anholt’s ability to draw readers into an actual story about the artists’ lives. Anholt exhaustively researched his subjects, and in each book he recounts a real-life friendship between a child and a famous painter. These stories are often tinted with moments of sadness as the artists contend with hardships in a fallen world. Edgar Degas, brooding and prone to angry outbursts, grieves the failure of his vision. Van Gogh and Cezanne, both solitary and misunderstood, duck when townspeople hurl insults and even projectiles at them. Matisse’s vibrant mind lives in spaces of color and movement, but he finds himself bedridden as his health declines. In all cases, Anholt offers a window into the brokenness of the world, with a sincerity that waxes more poignant than cynical.

In each book, however, we also glimpse moments of hope. The friendships between the artists and the protagonists are flickering lights in the darkness, hinting at the good, the true, and the lovely that will break with the dawn. Anholt ascribes to Buddhism, but the narratives he relates point to the Christian hope that although for now we groan (Rom. 8:22), hope burns on, and the Light will come. Furthermore, we witness the artists create some of their most breathtaking work in the midst of their trials. Such moments point to the truth that God can coax blooms from the ashes, and effect good even when the shadows descend (Rom. 8:28).

My daughter chased after a sculpture in a gallery because she knew the story behind the piece of art. Anholt’s books offer a beautiful avenue to explore such stories with our kids, and in so doing, to point them to the Creator who paints the horizon each evening, and who sculpted Everest skyward.

- Writing for His Glory: Meditate on His Word - March 20, 2024

- Writing for His Glory: Eyes to See - February 26, 2024

- These Fragile Remembrances - January 8, 2024

Leave a Reply