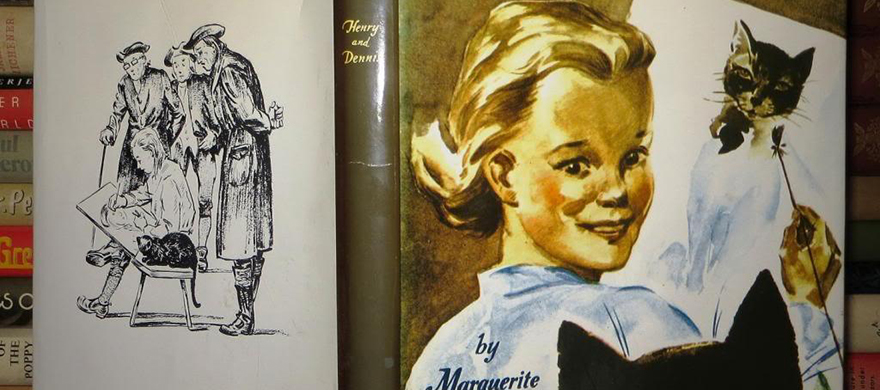

We read lots of historical fiction to our children. Most books were good at imparting information, some were rich in explanation, some filled us with inspiration, but only a few captured our imagination. It took a true storyteller to do that. The words “history” and “story” are from the same Latin and Greek root words, so the best history comes wrapped in a story, not canned in a textbook. And Marguerite Henry was one of our family’s favorite storytellers (1902-1997, author of 59 children’s books, most of them about horses).

We are not a cat family, but when you find yourself stuck in a cabin on a hillside in Gatlinburg, TN during an unanticipated snowstorm, with three teens and a seven year-old, you make exceptions. Everyone now remembers a cold afternoon, hot chocolate, and warm blankets to snuggle under on the couch as we read a 1947 story about a 1747 boy, Benjamin West, and his saucy cat Grimalkin.

Even if you know nothing about the man Benjamin West (more on him later), the fictionalized story of this slice of his childhood life draws you in and makes you want to keep reading to learn the fate of this young boy we meet first at seven years-old. Benjamin was the son of devout Quakers in the then-province of Pennsylvania (his maternal grandfather was a counselor to William Penn). Quakers were uncomplicated believers who valued simple living, hard work, and useful skills. And as a good and faithful Quaker, Benjamin’s Papa considered pictures and images to be frivolous, unnecessary, and worldly distractions. And therein, for Ben, was the rub.

Benjamin grew up in the countryside at the Door-Latch Inn run by his parents. There were no pictures, paintings, or images on its walls, and drawing was strictly discouraged in the West house. And yet at seven years-old, despite the visual austerity of his surroundings, Benjamin had an Irresistible urge to begin drawing, and to do so with obvious giftedness. Everything became useful in his hands in the absence of proper artist’s tools—Papa’s quill pen, charcoal, colors made from bear grease and clay with the help of his forest Indian friends, and even Grimalkin’s fur famously clipped to make “hair pencil” brushes for painting. The artist in the young boy could not be contained.

Marguerite Henry’s delightful story of how Benjamin West’s God-given talent sprouted, blossomed, and grew naturally like a wild flower in the forest is told with historical details and dialects, and with great human insight. What enriches this story is not only the progress of Benjamin’s art and how he felt about it, but also the softening of his strict but loving Papa, the encouragement of his quietly supportive Mamma, and the help of his connected uncle Phineas. There is a tenderness and joy in the telling that will warm your family’s heart with the picture of a very different, but still the same, eighteenth century family’s love for their artistically gifted child.

What captured our imaginations in the reading of this story was the true part about Benjamin’s artistic skills and motivation. They were clearly gifts from God, not the result (in modern lingo) of behavioral or environmental conditioning. He did not come to the world as a tabula rasa, a blank slate; rather, he came as a tabula scriptum, with markings on the slate. The finger of God had already written “artist” in Benjamin’s mind and spirit. And isn’t that, in part, what it means that we bear God’s image? We share markings in our person-ness from the Creator and creative God. “For You formed my inward parts; You wove me in my mother’s womb…I am fearfully and wonderfully made” (Psalm 139:13-14). The story of Benjamin West is a quiet, Quaker testimony to the work of God’s hands in our lives.

Of course, being the intuitive family that we are, those thoughts launched us on an imaginative exploration of what that truth means in our family, and in our children’s lives. What gifts has God written onto their slates (art, music, writing, math, science, physical, helping, technical, whatever)? How could we release those gifts and help them to grow? How could each child glorify the Giver of the gift through its use? How could we imagine God using those gifts to touch the lives of others, and even to change the world? We followed our imaginations, and still do, because Benjamin West did.

And who is the man Benjamin West? Born in 1738, the little boy with the cat-hair brush went on to become the father of American painting, known for his portraits, classical works, vibrant historical paintings, and later in life his religious paintings. He is the only American to have served as the President of the Royal Academy of Arts in England, from 1792 until his death in 1820. Many American artists studied under him in London, including Samuel Morse, Charles Willson Peale, and Gilbert Stuart.

And late in his life, he nostalgically remembered his cat Grimalkin. We may not be a cat family, but after reading this story we might have made room for a Grimalkin. Now that’s using my imagination.

- Disruptive Imaginology - February 11, 2019

- Benjamin West and His Cat Grimalkin - March 7, 2018

- Use Their Imagination - October 2, 2017

Another book to add to my list of read-alouds! Thank you!

Clay – Thank you! Whenever I find an extra copy of this book, I buy it to give away. I was stopped by the fact that the “first American painter” had never seen a painted picture, yet he knew that he was born to paint. What a contrast against our culture which plots and plans the activities and futures for our children. His story is amazing.

For those who are close to Greenville, SC, Bob Jone University owns a collection of West’s paintings. They are stunning (and huge).

For those who read the book, consider clipping a tuft of hair from your cat (or dog) and making a paintbrush (then paint with it). My kids had a blast, and although we may forget the specifics of West’s life, we won’t ever forget his larger story.

Ooh! We live in Asheville, NC just a 1.5 hours away from Greenville! Thanks for the tip. I’m looking forward to making a summer adventure out of this!

I have this book on my shelf in my classroom, given to me by the school I teach at for a potential read aloud. In three years of teaching there, I’ve yet to read it to my students, but I most certainly will now! Thank you!

I love Marguerite Henry, and I’ve seen this one, but never read it. My kids would love it!

Our family vacations in Chincoteague every year so I’m well acquainted with her Misty books. I never heard of this one! It sounds fabulous! My kids have a similar memory in that we are not dog people, but we cried our eyes out when I read Stone Fox aloud. Thanks for this recommendation.