Last month we had to put a beloved cat to sleep.

Her name was Captain Jack Sparrow, and she was one of two littermates my husband and I adopted early in our marriage when we decided, on a whim, to stop by the pet store just to “look at the kittens.”

Sparrow was a gray and copper tortoiseshell with sprinkles of white on her nose, chest, and paws. If one of us was sad, she knew: she’d find the woebegone one and puddle in her lap, purring like an oversize bumblebee until the suffering one, in spite of herself, began to smile a little. She scratched at bedroom doors in the middle of the night until we let her into her room of choice, where she’d drape herself over a sleeping inhabitant and set the mattress thrumming with her purr. Sparrow preferred her water fresh from the bathroom tap, and she’d meow in a rich contralto until we turned the tap on for her. She was awkward and charming, and she and I understood one another. Our family decided that if she had an epitaph, it would have to be a modified quote from James Herriot’s Moses the Kitten: “She was a connoisseur of comfort.”

Sparrow was sixteen years old; she died quietly, dwindling from the round cat she had been to a frail form who still purred feebly whenever someone looked at her. Her brother continues to scale six-foot fences and scrap with the neighborhood dogs like he intends to live forever. As these things go, it was a best-case scenario—but everything about it was wrong.

Our little loss is, of course, nothing compared to the harrowing separations those around us have faced over this past year and a half. But it awakens in me a lament: It isn’t supposed to be this way. Death isn’t random; it’s not meaningless; nothing about it is natural. We love with the knowledge that what we love will pass away—even children learn to worry about this. Something in us cries out for permanence, for the assurance that what we love will persist in some way. We long to love without loss.

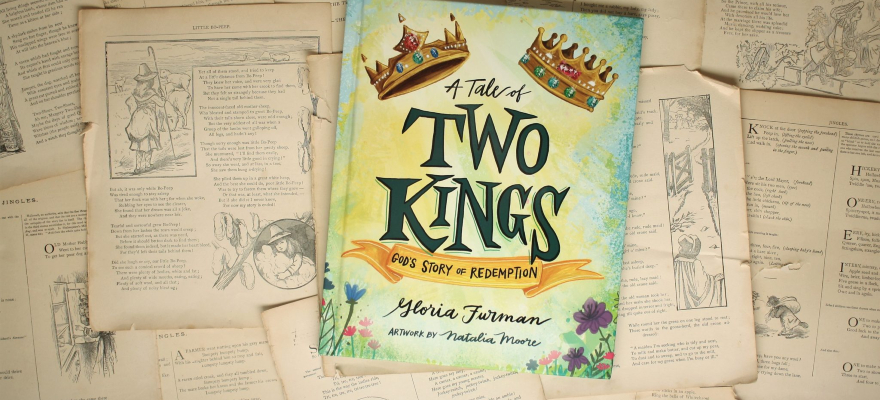

Gloria Furman—author of many excellent books for adults—understands this. She knows the world isn’t supposed to be this way, and in A Tale of Two Kings she assures families that it won’t always be this way. Through this picture book contrasting the lives of Adam and Jesus, Furman shows us both how the world was broken (through Adam’s failure to fulfill his role as king) and how it is, already, being redeemed through Jesus, our perfect king.

This book is a slender presentation of the gospel and of the entire narrative arc of Scripture. Natalia Moore’s illustrations bring these deep truths to life, and Furman writes to her young readers with the same theological richness evident in her books for adults. “We have nothing to fear,” she writes at the end of A Tale of Two Kings. “Instead, we can have a great hope! Jesus is greater than anything scary and sad—he is greater than all the world. We can trust Jesus, the King who is making all things new.”

I don’t know if our cat has a place in the new heaven and earth; if she does, it will be in an unmovable patch of sunlight. But I do know that our God cares for his creation—sparrows, Sparrows, and all. I know that any loss we face, whether large or small, is a symptom of Adam’s failed kingship, not a whim of an impersonal universe. And I know that Jesus, our true and perfect king, is repairing what broke in the fall. He is making all things new.

“Come, Lord Jesus!” (Rev. 22:20)

A Tale of Two Kings: God’s Story of Redemption

Gloria Furman; Natalia Moore (2021)

- The Mousehole Cat - April 3, 2024

- Review: Jesus and the Gift of Friendship - March 27, 2024

- Review: James D. Witmer’s A Nose For Trouble - December 4, 2023

Leave a Reply