NOTE: This piece first appeared in The Rabbit Room, and then on Story Warren in 2013. It seems fitting to re-visit it now.

So my nine-year-old son Aedan just finished reading Tolkien’s The Return of the King for the first time.

He came downstairs after he finished and we talked about the ending, about the mysterious Undying Lands to which the elves were compelled to go; about how happy and sad he was for Sam, who had a family and a home in a restored Shire but who had to go on without his dearest friend; the bittersweetness of Frodo’s farewell at the Grey Havens. I can’t imagine a more poignant or complete ending to the story.

I told him that Ben Shive wrote a song about the Grey Havens, and I played him that song from The Far Country while he read through the lyrics. (I don’t normally push my own music on the kids, so he wasn’t too familiar with it.) I was impressed all over again at what a great writer Ben is, not to mention Tolkien.

What is it about that idea of being wounded and ill-at-ease in our present condition that resonates with me so? Obviously, it’s because I’m wounded and ill-at-ease. Much of the time I feel content with my lot, and why shouldn’t I? Most of the people reading this have been blessed with the means at least to own a computer, and the leisure at which to browse websites with it. You have the ability to read, to see, to think, to type. What could we complain about? Well, about the fact that our hearts are crippled and weak. Our literal eyes may be able to see, but the eyes of our hearts are often so bloodshot and weary that our souls trip and fall.

Sunday’s sermon was about Hope. Hope is not the same as optimism, the pastor pointed out. Optimism has its place, but it is at its core the name given to a way of looking at things. The glass is either half full or half empty–our opinion of it doesn’t change the amount of water in the cup. Sure, it changes our disposition, and of course an optimistic one is the better of the two. But Hope goes deeper. Hope gives thanks that there is such a thing as water, and remembers that whether the glass is empty or full, there is a greater story being told. If there is water in the glass, then somewhere beneath the earth, in cathedral caverns where no eye has yet seen, a clear river courses. I may cry out in pain or sorrow (which seems to me anything but optimistic), and yet have hope, though I cling to it feebly.

Hope lies deep and silent.

Aedan’s reward for finishing the book was that we all watched The Return of the King–all seventeen million hours of it–Saturday night. The book itself is so precious to me that the movies, though they’re perhaps as good as they could ever hope to be, pale in comparison. But I was moved to tears several times this Saturday night, sitting next to my wife and my boys with the volume turned up way too loud. The couch rumbled. I didn’t marvel so much at the movie (though it really is a marvel in so many ways) as the story itself. This has been beaten into the ground, I know, but–what a story! What a gift Tolkien gave us.

I kept watching Aedan and Asher’s faces during certain parts of the movie, like when Shelob poisons Frodo and Sam feels that all is lost. The boys were looking upset, so I paused the DVD and talked to them about eucatastrophe. It’s a word Tolkien coined in his essay “On Fairy Stories” which means, basically, the opposite of catastrophe. He calls eucatastrophe the “sudden joyous turn”. It’s that moment when all seems lost, when evil seems to have finally overcome every good thing, when the hero can go no further. Then light prevails against the darkness. The good guys win.

When you’re writing a story, like I am now, you realize that there’s not much story if there’s nothing at stake. If there’s no evil, no enemy, no point at which the hero is at the end of his rope, then the thing falls flat for some reason. But if we want the good guys to win (and almost universally we do), why do we put our heroes through so much? Because we grow into what we are meant to be by walking through the fire.

I told the boys about how the story of Jesus’ resurrection is the ultimate eucatastrophe. When Jesus, the perfect man, God made flesh, cries out and exhales his dying breath, the sky is black and roiling, the ground shakes, the dead emerge from their tombs and haunt Jerusalem, and the sheep scatter. But Sunday morning, more than just the sun rises. Everything changes. It’s not just a story, it’s the story. A sudden joyous turn, indeed.

Un-pause.

Gandalf is sitting with Pippin beside a bulwark, a scared and weary Pippin says, “I didn’t think it would end this way.” Ian McKellen, who as far as I have read is hostile toward Christianity and Christ, speaks through Gandalf such a moving description of Heaven that I pause the movie again. Rewind. Turn on subtitles so the kids can read it. Play.

Gandalf: End? No, the journey doesn’t end here. Death is just another path. One that we all must take. The grey rain curtain of this world rolls back and all turns to silver glass. And then you see it.

Pippin: What, Gandalf? See what?

Gandalf: White shores…and beyond, a far green country under a swift sunrise.

Pippin: Well, that isn’t so bad.

Gandalf: No. It isn’t.

Then comes the sound of the door being battered down by trolls and orcs. Pippin and Gandalf are snapped out of the dream back into the present, and Pippin closes his eyes and swallows. How well I know that feeling, the feeling of taking a deep breath and bearing up a little longer for the sake of the hope and great joy that lies before me.

The kids looked at me sideways, wondering why their dad was sniffling.

Finally, Frodo bids his friends goodbye at the Grey Havens. I didn’t pause it this time, but as soon as the film was over I talked with Jamie about the wound that we all carry. Just like Frodo, we have wounds that are too deep to heal this side of that grey rain curtain; the wounds of the Fall, of our daily sin, of our loneliness and selfishness and tendency to believe the lie over the Truth. I ache to board that ship and sail away to those white shores and that far green country.

Hope holds me up. It’s what I cling to, and all I ever want to cling to.

“We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time. Not only so, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for our adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies. For in this hope we were saved. But hope that is seen is no hope at all. Who hopes for what he already has? But if we hope for what we do not yet have, we wait for it patiently.” (Romans)

Lord, give us patience.

—– —– —–

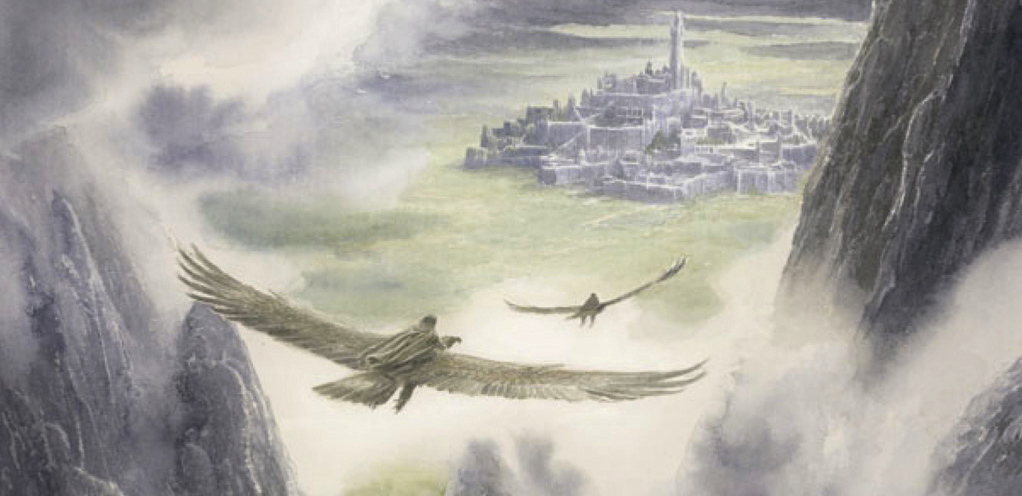

Featured image cut from an Alan Lee illustration

- A Sudden Joyous Turn - July 29, 2020

Love this story! – And this essay; excellent job cherry-picking some of my favorite themes and scenes.

Thanks, AP and SD for collaborating.

Man. So, so good. Thanks for not letting this get lost in the Rabbit Room archives, Sam and Andrew.

(Also – goopy plasma cereal. Perfect.)

Love this. Living right in the midst of that ache has been a marker of these last few years for me: learning to let hope and longing grow right along side the art of dailiness and gratitude. Loved the connections you made here.

So, so good! “I ache to board that ship and sail away to those white shores and that far green country.” Me too!

What a beautiful essay. I remember well the first time I read the final chapters of The Return of the King (I was eleven). The story of Frodo, post denouement, haunted me. I remember the creeping dread at seeing Frodo gradually drop out of the life of the Shire — not quite as acute as the dread that attended, say, the Black Riders approaching Weathertop, but no less real. The end of Sam’s story made sense; Frodo’s, none at all. Every story I’d heard had prepared me for Sam’s ending; none had prepared me for Frodo’s. It’s Frodo’s ending, though, that prepared me for the story I live in. Andrew’s final paragraphs go a long way to getting at why.