As I recall her in my mind’s eye, Mrs. Thompson (first name lost to time) was a pleasantly plump, nurturing fifth grade teacher, clad in the sort of festive, seasonally-appropriate sweaters favored by seasoned elementary school veterans. During my first year at that small Christian school in Winter Park, Florida, she led my class through math and science, handwriting and Bible. And, she also had the distinction of bringing me face to face with death for the first meaningful time, through story.

My childhood, while not idyllic, was nonetheless, relatively free of loss. My dog Mac had died in the night on Valentine’s Day earlier in my grade school years, but to that point, I had never lost a close friend or relative. I suppose the greatest sense of loss I routinely experienced as a child was leaving behind friendships due to nearly a half-dozen moves before third grade.

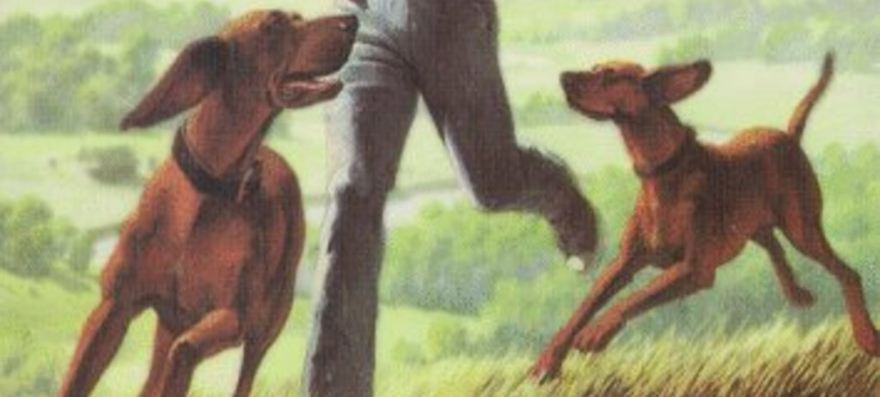

So Mrs. Thompson reached the final chapter of Wilson Rawls’ Where the Red Fern Grows after weeks of reading aloud to our little class community, and first Old Dan, then Little Ann, left Billy behind after that run-in with the mountain lion. And something inside of me which I hadn’t even known existed, broke. The bond I had formed with these two brave hounds, tirelessly loyal to the very end, was stretched until it snapped. At the time, I probably couldn’t form my feelings into words. So I wandered through days poring over the ending of that story, trading anger for grief, until the emotions subsided, and I passed through a door into a new room, face-to-face with the reality of loss.

For others, it’s stories like Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ The Yearling, or E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web that took them by the hand and led them into that room, a first encounter with death in all its gnawing emptiness. And, as I’ve come to learn all too well in the thirty-some years since that day, death is not a bloodless, painless concept, an abstraction to be considered intellectually, then dispatched. Death leaves marks on the living. Each loss is different, the grieving process unique, with no way to understand how until one experiences it. And for a child, who may or may not have experienced actual death in their real life, experiencing death through stories is vital.

A few years ago, we watched some old episodes of the Jim Henson series Fraggle Rock. In a first-season episode called “Marooned,” two Fraggles, Red and Boober, are trapped in a cave-in, far from home, with the grim realization that no one knows where they are or will be coming to rescue them, as their oxygen slowly runs out. We watched this episode on a car trip, my two boys in the backseat, and Red and Boober’s conversation drifted to me in the front.

“We’re running out of air,” Red notes, before asking Boober, “What do you think it’s like to die?” Boober answers her,

“I don’t know, Red. I don’t think anybody does. You know, I remember this one day, I was doing my laundry, and then this big soap bubble floated right up from the tub, and there is was, in front of my face, beautiful and shiny, and then it was gone.”

There’s a long pause while Red cries, and Boober tries to reassure her. The moment hangs in the air, raw and fragile, and the two huddle together, waiting for the end, until they’re rescued by their Fraggle pals.

I was chilled hearing this conversation, and a bit horrified that it had crept up on me without my having had time to prepare. But then, I let out the breath I was holding in. It was going to be okay. We could talk about it. And we did, just like we did when Charlotte performs her final heroic act to save Wilbur’s life there in that county fair pig stall, or when Sarah Ruth, whom Edward Tulane has loved so dearly, finally succumbs to her lung disease.

Confronting death in stories can be scary, but when it occurs in a supportive environment with conversations that bridge the gap between the waking dream of fiction and the incarnate world around us, it’s a vital part of the maturing process. Stories aren’t giving our children anything they don’t already see around them. The hollowness that comes with mourning someone, even if they were fictitious, feels real, as the story makes them real. That’s great practice for living with the haunted reality of loss. We learn the great truth, as expressed by Jason Gray: “Yet in our grief we know death must be a liar/For no goodbye is ever good enough.”

That emptiness can lead us to a greater hunger for life, and a hunger for our true country, the world beyond the sky. As Aslan tells the Pevensie children in the final chapter of The Last Battle,

“The term is over: the holidays have begun. The dream is ended: this is the morning.”

The Last Battle, C.S. Lewis

Calling this world the Shadowlands is perhaps the best name I know for it. Even our own world, in all its color and wildness, is a story-world of sorts. And we will move beyond it one day. We hunger for stories here because we hunger for life, and truth. And here’s a truth: death is cruel, but it’s also a ruse. As N.D. Wilson puts it, “Death is grace. Beause of death, we can run the good race. We can fight the good fight. Completion exists.”

The End is not the end. Not in stories. And not in our story. Take heart.

- The Winter King: A Review - January 10, 2024

- Taking it Slow - November 13, 2023

- Calling Out Your Name: Rich Mullins, the Rocky Mountains, and Tumbleweed - October 17, 2022

Leave a Reply