My family and I serve as missionaries in Mozambique. Most Sundays, we’re out in one village or another, the five of us worshipping under a thatch roof with a local church. I usually end up preaching to a few dozen people, communicating in a language that is not my native tongue.

The people we’ve worked with in this corner of Africa over the past 14 years are predominantly first-generation Christians; most of them can’t read. So, it’s not too difficult to feel inadequate to the task. Here I am trying to communicate the epic stories of Scripture across multiple cultural and linguistic barriers… while chickens and goats and the occasional drunk person wander in and out of the assembly. Now, this may sound a bit strange, but there’s an ancient communicator that I’ve found myself thinking a lot about lately: Homer.

You remember him, right? Ancient poet… Iliad and Odyssey… high school English class… Right! It’s been inspiring to think about the connection between Homer and Homiletics, the Epic Poet and the Exercise of Preaching. His example has helped me understand my place.

Homer’s two classic stories, the Iliad and the Odyssey, reflect, in my mind, the essential task of communication: calling hearers to join a battle, the conflict (Iliad), as well as challenging them to persevere in the journey back home, the crossing (Odyssey), where upon their return, they’ve been changed. I’m trying to see the role of preaching through the lens of the epic poet. Adam Nicolson notes,

“Epic’s purpose in our lives is to make the distant past as immediate to us as our own lives, to make the great stories of long ago beautiful and painful now” (The Mighty Dead: Why Homer Matters, page xix).

Homer has helped me understand my vocation as poet and that what I have to communicate is of epic proportions and power.

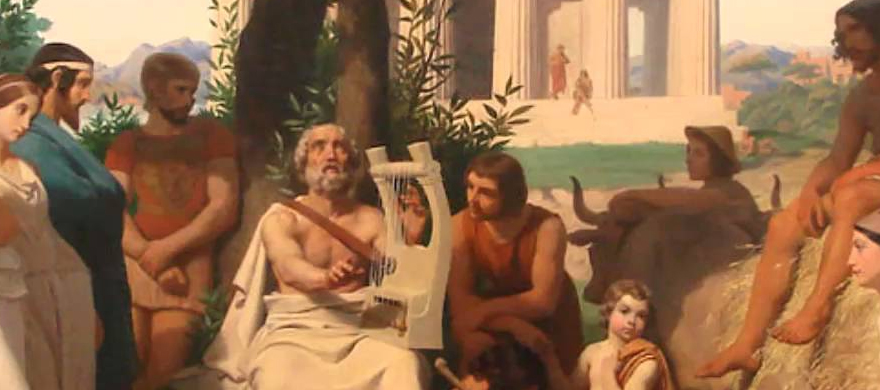

There is a picture in my study, a gift from my sweet wife. It is a copy of a fresco from a Mycenaean-era palace in Greece. Nicolson describes the depicted scene evocatively:

“Against a ragged background, perhaps a rough, mountainous horizon, a poet—call him Homer—sits on a luminous, polychromed rock… dressed in a long, striped robe with the sleeves of his overshirt coming almost halfway down his bare brown arms. His hair is braided, tendrils of it running down his neck and on to his back. He looks washed. Everything about him is alert, his eyes are bright and open, his body poised and taut, upright, ready. In his arms, he holds a large five-stringed lyre, the fingers of his right hand plucking at those strings, which bend to his touch.

“Against the florid red of the wall behind him… is the most astonishing part of this image: an enormous, pale bird, the color of the bard’s robe… its eyes as bright and open as Homer’s, its body larger than his, its presence in the room huge and buoyant, nothing insubstantial about it, making its way out into the world, leaving Homer’s own static, singing figure behind. The bird is poetry itself taking wing, so big, so much stronger than little Homer… his fingers on the lyre. It is the bird of eloquence, ‘the winged words’, epea pteroenta… epea having the same root as ‘epic’, pteroenta meaning ‘feathered’: light, mobile, airy, communicative. Meaning and beauty take flight from Homer’s song.” (xx)

Being a communicator means believing that the words we speak have power. When we have something meaningful to say those words are real and have the force to bring worlds into being for the hearer. That image of Homer has inspired me to communicate with confidence.

Let’s hear more from Nicolson on the significance of that fresco,

“It is one of the most extraordinary visualizations of poetry ever created, its life entirely self-sufficient as it makes its way out across the ragged horizon. There is nothing whimsical or misty about it: it has an undeniable other reality in flight in the room. There is a deep paradox here, one that is central to the whole experience of Homer’s epics. Nothing is more insubstantial than poetry. It has no body, and yet it persists with its subtleties whole and its sense of the reality of the human heart uneroded while the palace of which this fresco was a part lies under the thick layer of ash from its burning in 1200 BC. Nothing with less substance than epic, nothing more lasting. Homer, in a miracle of transmission from one end of human civilization to the other, continues to be as alive as anything that has ever lived.” (Nicolson, xx)

While it is right and good for Nicolson to marvel at the impact of Homer and his poetry, there is a poet whose song and story have had an infinitely greater impact. The first Poet, the Lord of creation, spoke worlds into being. That Word then put on flesh and moved into the neighborhood (John 1:14) and even now continues to hold the cosmos together (Colossians 1:16). And his poem continues winging its way through our world bringing life and love. So I’m trying to understand my vocation of Preacher as Poet. I’m trying to remember that these words have power. Meaning and beauty take flight from this epic song, winging their way into the heart of the church.

You may not be a preacher by trade, but if you’re reading this you probably have a little congregation that meets under your roof. And as one of the “communicators-in-chief” of your household, you have the gift and challenge of speaking the epic stories into the hearts of those children.

I wonder what would happen if we understood the vocation of Parent as Poet, taking seriously the truth that words have power; believing that we really are somehow, miraculously made adequate to the task; knowing our place and confidently speaking the epic stories of Scripture into our family; inviting our children to join the conflict and the crossing to home; watching that song take flight and empower them to live into God’s epic poem.

- Sir Raleigh, Storytelling, and the Sea - June 19, 2023

- The King and the Kids’ Table - October 18, 2021

- Encouraging the ‘Why’ - August 9, 2021

Thank you! This is a beautiful idea to ponder and practice. The Lord bless your family in your ministry!