Dear Story Warren readers,

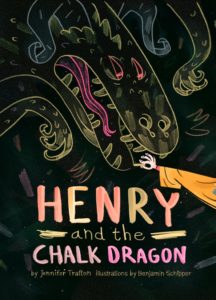

You are in for a treat today! I’ve gotten to know Jennifer a bit through The Rabbit Room, and I think of her as our own Miss Rumphius come to life. Whether it’s hosting an arts day for women in her home, creating beautiful spreads in her bullet journal, teaching little ones how to creatively see the world, or bringing a hilarious, joyful young boy named Henry to life, Jennifer Trafton is filling her part of the world with beauty, day by day. I’m so excited to bring you this interview with the author of the new release Henry and the Chalk Dragon (available at The Rabbit Room and Amazon).

You are in for a treat today! I’ve gotten to know Jennifer a bit through The Rabbit Room, and I think of her as our own Miss Rumphius come to life. Whether it’s hosting an arts day for women in her home, creating beautiful spreads in her bullet journal, teaching little ones how to creatively see the world, or bringing a hilarious, joyful young boy named Henry to life, Jennifer Trafton is filling her part of the world with beauty, day by day. I’m so excited to bring you this interview with the author of the new release Henry and the Chalk Dragon (available at The Rabbit Room and Amazon).

First, can you introduce yourself to our Story Warren readers?

Certainly! What shall I say? I’m a writer of stories, a reader of books, a teacher of young’uns, a drawer of drawings, a letterer of letters, a keeper of chickens, a cuddler of dogs (one dog in particular), an eater of chocolate, a drinker of tea, a sailor of boats, a lover of colors, and a wife, daughter, sister, sister-in-law, aunt, and friend of a whole passel of tremendously interesting and talented people. I’m also scared to death most of the time, which is why I seem to keep writing stories about bald-headed worriers and people who need to be brave.

Can you talk about yourself as a child? Who or what encouraged you on the path to becoming an author?

I was, in many ways, the girl version of my main character Henry in Henry and the Chalk Dragon. I was most myself in my bedroom alone with my books, my art, and my imagination. Going out into the wider world—and certainly talking in that world—was a much greater challenge. I had a wise preschool teacher who saw this tendency of mine to withdraw into my own inner imaginative world, and she advised my parents never to let me shut the door of my bedroom, because I would get lost in my solitude. (She basically predicted the whole subsequent struggle of my life.) But even with my door open, that room was my sanctuary and the setting of my adventures – the bed was a vast mountain, the carpet a desert, the stuffed animals a whole cast of heroic or unsavory characters.

I didn’t care two hoots about my Barbie dolls’ fashion sense—I sent them on quests and hung them upside-down by their ankles in evil witches’ dens under the desk, left there to struggle free and rescue their friends. I remember my mom peeking her head into the bathroom once to check on me because I’d been in there for hours making up adventures with my dolls, with the bathtub as the sea and the sink as a dolphin tank. I’d pretend I was a spy and sneak around the house, hiding in corners and eavesdropping on conversations (I don’t think my family ever knew this! I might have to come clean . . . ) I couldn’t wait to go to bed at night, because as soon as the light was off I could retreat safely into my imagination, where no one would interrupt me or see me. And each night in the dark of my room I would return to the sagas of previous nights’ imaginings and make up the next scene in the story. They’re so vivid I still remember some of them. I really think, looking back now, that those secret bedtime sessions were the time when I was training my imagination to be a storyteller.

I usually point to fifth grade as the year when imagining turned to writing in a deliberate way. I took a creative writing class that year, and my parents gave me a blank journal in which I recorded my poems for the next several years. In high school I began actually finishing the stories I started, and without ever really making a decision to do so I wrote picture books and funny children’s stories — that’s what naturally came out of me.

But as I grew older, although my teachers always praised my writing, just about every attempt to send my writing out into the world was met with rejection — my poems and stories were rejected by magazines and publishers and prize committees, I was rejected for summer writing programs, and I just never fit in with other kids my age who loved writing. It felt like I was a Shel Silverstein in a world of teenage James Joyces. Discouragement came early and hard, and I began to think that writing was a nice pipe dream but of course I needed a real career. The path after that was long, convoluted, and marked by numerous binges on Double-Stuff Oreos. But there was a moment in my late 20s when I had hit rock bottom and my dad said to me, “You could have a career as a writer. But you have to write something.” So, while my parents graciously let their 27-year-old daughter live with them without a job for a while, I wrote The Rise and Fall of Mount Majestic. And the rest is . . . well, let’s just say there were still a lot of Oreo binges after that.

Authors often talk about knowing their characters long before they ever come to life on a page. When do you first remember “meeting” Henry Penwhistle (the hero in Henry and the Chalk Dragon)? What was the process like for you as he became fully formed?

I recently came across the very first notes and early drafts of this story (from six years ago) tucked away in a dark corner of my computer, and there was a fun “Oh yeah, I’d forgotten about that!” moment.

I recently came across the very first notes and early drafts of this story (from six years ago) tucked away in a dark corner of my computer, and there was a fun “Oh yeah, I’d forgotten about that!” moment.

Henry wasn’t an artist at first. He was the Knight of the Purple Pajamas, going on a quest in his own home, chasing a sneaky dragon who kept disguising itself as a sofa, a can opener, a sculpture, a pair of rain boots, a pile of dirty laundry, a rug, etc. And Henry outsmarted it by showing that he also could be many things — a knight, a spy, an explorer, an astronaut, a janitor with a dragon-sucking vacuum cleaner. The earliest seeds of the story had to do with all the shapes a child can be, all the shapes his imagination can take.

At the time, I was a little bit obsessed with the musical “Man of La Mancha” (based on Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote). Remember that song, “To dream the impossible dream?” I started thinking about this character of Don Quixote and how his crazy imagination turned the world around him into something else, something epic and noble, and I thought, That’s exactly how I played as a child. Beds are mountains, and windmills are giants. With a little imagination, a cardboard box can be anything in the world. There’s a shimmer of magic and mystery over the commonest things. I suppose that’s the spiritual gift of mad knights and children.

So when he first popped into my brain, Henry was already named Henry, he was a knight on a quest, and he saw the world double, so to speak—the literal world, and the imaginative one. I wondered, could I write a story that was basically an eight-year-old’s imagination turned inside out? As the story developed, it seemed only natural that Henry would love to draw, and the fantasy of every child who has ever drawn a picture is that his art would come to life. We’ve been telling that story from the myth of Pygmalion onward—but I wanted to explore the wild silliness and the deeper complexity of that longing in a boy like Henry, who’s a shy child (and a fearful artist) like me.

Henry and the Chalk Dragon is full of little references to other works of children’s literature. What are some of your favorite recommendations for young readers in the same age bracket as Henry?

Yes, I had fun dropping little literary Easter eggs everywhere! Henry’s imagination has been nurtured by classic stories just as mine was, and Henry and the Chalk Dragon is, in a way, my homage to the things that shaped me. Here are a few books (mostly old but a few new) I often recommend for younger elementary readers:

- Anything by Beverly Cleary — my favorite was always The Mouse and the Motorcycle

- Anything by Edward Eager or E. Nesbit

- Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach (my favorite of his books)

- E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web and The Trumpet of the Swan

- Kate DiCamillo’s books — especially Because of Winn-Dixie (which I consider to be a near-perfect children’s book), The Tale of Despereaux, and the Bink and Gollie books

- Marjorie Weinman Sharmat’s Nate the Great series

- Sara Pennypacker’s Clementine series

- Ruth Stiles Gannett’s My Father’s Dragon

- L. Frank Baum’s Oz series

- Louis Sachar’s Wayside School books

- Mary Norton’s The Borrowers (and sequels)

- Sid Fleischman’s The Whipping Boy

Oh dear, I might never stop. I love this age level. And of course, there are wonderful books for kids by writers associated with the Rabbit Room and Story Warren — Jonathan Rogers, Andrew Peterson, Sam Smith, Doug McKelvey, Jonny Jimison.

This book is a delightful celebration of a young child’s imagination. How can the parents among us cultivate imagination and creativity with our little ones?

I’m not a parent, so I’m always a little reluctant to tell parents how to be parents! But let me answer this question as a daughter. My parents have three children: one grew up to be a writer and artist (me), one grew up to conduct operas and symphonies in Germany, and one grew up to be an actor who has performed on Broadway and now creatively incorporates the arts into his ministry as a church youth director. How did my parents do it? What magical food did they feed us, that all three of us eschewed more normal and practical career paths and chose to follow our wild imaginations in these weird creative directions? I’ll probably never fully know the answer, but I can make a few guesses.

For one thing, they read aloud to us and encouraged our love for books from a very early age. I can still remember my mom reading chapters of The Swiss Family Robinson and The Neverending Story before bed while my brother Joe and I begged for more, and my dad read the Narnia Chronicles to me so many times that Aslan still speaks in his voice.

For one thing, they read aloud to us and encouraged our love for books from a very early age. I can still remember my mom reading chapters of The Swiss Family Robinson and The Neverending Story before bed while my brother Joe and I begged for more, and my dad read the Narnia Chronicles to me so many times that Aslan still speaks in his voice.

We’d go to the library regularly and bring home towers of books, and we had one of those houses that oozed bookshelves from every spare wall. I can’t emphasize enough the importance of this family literary culture for nurturing the imagination—my childhood was thoroughly soaked in words and stories.

As soon as our unique interests began to emerge (my brother Joe, the future opera conductor, was listening intently to musical scores even before he could read!), my parents found ways to encourage and enable us to pursue them.

Even though money was always tight, somehow there was a piano in the house. Somehow there were art classes and violin lessons. Somehow there were summer programs and theatre opportunities and colleges where we could study what we were passionate about (not just train for jobs). I know that required a lot of sacrifices on their part and they couldn’t provide everything, but they made sure that if we found something we loved to do, there was a way for us to do it. And they never said, “Art? Acting? Operas? How do you make a living doing that? Those are fine as hobbies, but you need a real career.”

Instead, all I remember is affirmation. They were the first ones in the door at every concert, every performance of every play. They praised every picture I drew and every poem or story I wrote. They were behind us pushing us onward.

I love it, as a creative writing teacher, when I encounter parents who don’t consider themselves to be “creative” (though I would disagree with them on that point) but who see the flicker of creative passion in their children and are trying their best to figure out how to fan that flame. A mom comes to me and says, “My son spends all his time reading and writing stories, and I want to give him more opportunities to develop that, but I’m not a writer myself and I don’t know how. What should I do?”

That’s a parent whose child is going to flourish, because she’s not trying to mold her son after her own image; she’s watching that personality and passion growing and she’s saying, “I want to help him be what he is meant to be.”

In Henry and the Chalk Dragon, that’s how I saw Henry’s parents — bemused by his imagination, maybe not completely understanding his art, maybe needing a little bit of imaginative reawakening themselves — but obviously giving him the space and materials to explore it and encouraging him to be the unique artist he is.

OK, now for the speed round:

What is your favorite thing to eat?

Chocolate brownies, without nuts. I’ve decided, after a lifetime of research, that moist, rich brownies (especially with bits of molten chocolate chips inside) are the best delivery system for chocolate. Amongst the non-chocolatey foods, my favorite is spaghetti and meatballs.

Can you tell us your pets’ names?

I have a border collie named Penny, a rooster named Tom Bombadil, seven hens named Babs, Henrietta, Clementine, Goodness, Mercy, Early, and Galadriel, and a duck (Mr. Meatball) who thinks he’s a chicken and who’s rather naively infatuated with Penny, who has a tendency to carry him around by the neck like a stuffed toy. We’re a happy family, until the coyotes come.

If we were to open up your purse/bag/backpack, what would we find out about you?

- I am extremely disorganized.

- I need lots and lots of Kleenex.

- I’m obsessed with pens.

- I’m terribly unprepared for an adventure, unless that adventure involves calligraphy or a runny nose.

- I forgot my wallet again.

Morning person or night owl?

Neither. I’m a middle-of-the-day gal. In other words, I love to sleep.

[You can find more from Jennifer at her website. Don’t miss the free curriculum guide to Henry -it’s great for families, homeschool groups, and classes alike! You can also find more information about the online creative writing classes she offers for children aged 8-14 during the school year.] — Kelly

- A Winter Book Basket - February 7, 2024

- Review: While Everyone is Sleeping - October 25, 2023

- Some Keller Family Favorites - September 11, 2023

So much fun! I like you two ladies a whole awful lot.

I will presume to speak for JTP and say we like you, too.

Let’s all speak for JTP! I’m sure she won’t mind!