Southy

by S.D. Smith, illustrated by Aedan PetersonSouthy was a mouse who stared out of windows. One window in particular was his favorite. When the people had gone to bed and the mice were searching through the house for crumbs, he would often ignore the mad scurrying below and sit with his arms under his chin and stare at the moon reflecting off the river in the valley behind the house. He didn’t like for anyone to know it, but occasionally, he would sigh and shake his head. The other mice, he believed, would never understand.

Life is hard for a mouse in a house, especially if the human residents aren’t messy. And the house where Southy lived was depressingly lacking in messy humans. They were neat humans who tucked in their shirts and mostly left the TV off. They read books aloud together after dinner and smiled a lot. They were very, very weird and annoyed the daylights out of the night-prowling population of mice.

“It ain’t natural!” Pooks said to the gang of mice gathering around the hole at 10pm. “See here, they go to bed so early, leaving the entire downstairs to us. But there ain’t much to choose from!” Pooks was a huge –almost-rat-sized– white mouse with a loud, barky voice and permanent, bitter frown.

“My cousin says he could feed his family for a year on the potato chips he finds in the couch cushions at the house next door,” Vint, a small brown mouse with a lisp, said.

Someone else tried to speak up, but Pooks barked out, “I have no doubt it’s true, Vinty. And most likely they are Doritos.” Pooks never liked to let two others speak in turn without getting in a few more words of his own. He was a mouse, sure, but also a hog.

“They aren’t so bad,” Southy said quietly, almost to himself.

“What was that, Softy?” Pooks barked. “None of us can hear your teensy squeaks, Softy!” They laughed and laughed. Southy looked down and shook his head.

“Leave him alone,” Nina, a small grey mouse, said. Then added, “You awful bullies.”

Pooks, hearing this, retorted with his own high-pitched mime of Nina, “Leave him alone!” and they roared, because simple-minded fools will always laugh if you just make a funny voice and repeat whatever a nice mouse has said. Nina sneered at them and Southy just shook his head. He started to speak a few times, but each time he closed his mouth again, then shook his head some more.

“I think Southy likes the people,” Vint said.

“He does, Vinty,” Pooks said, as if the realization was as delicious to him as a crumb-riddled couch. “His fur’s gone purple, he smells like a drunk skunk, his voice is softer than a squeaky baby, his head shakes like a bowl of jello, and he’s a tootin’ human lover!”

“Boooooo!” they shouted. And they proceeded to jeer Southy with cruel enthusiasm. They didn’t hiss, mice never hiss because of the association with snakes, but they clicked their tongues at him derisively and laughed like lunatics. Nina glared at them, but Southy only shook his head. The truth was his fur really was a little purple. But that had come from his adventures.

The laughter eventually died down and other subjects for discussion came and went as the mice crowded around the hole to wait for the light to go out and the last human to head upstairs. It couldn’t come soon enough for Southy, who was sad about his station in the mouse community and eager to be about his business.

His business was in the bottom of the house.

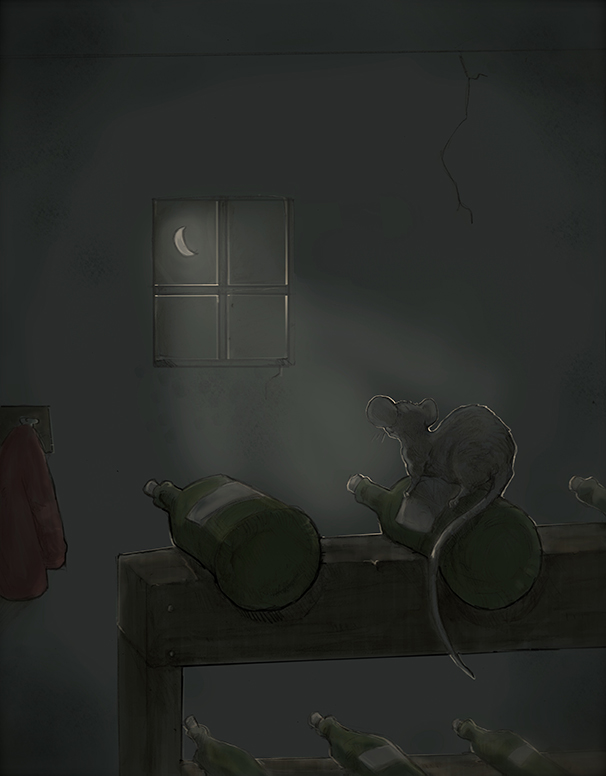

The lights went out at last and the mice quietly surged through the hole and spread out to find whatever scraps of food they could. Southy went for the door beside the pantry, checked to see if anyone was following him, and then slipped under the door. He found the stairs and went down, down, down into the quiet darkness of the cellar. There was only one small window letting in a thin sliver of moonlight. He stopped on the bottom step and stared up at the moon. He could have stayed for hours, staring at that beautiful moon, but he shook his head and reluctantly broke away from his gazing. He had a task to perform.

In the cellar he found racks of wine, neatly arranged and seldom touched. Cobwebs hung above the highest racks and dust settled over all. He noticed three broken bottles, still undiscovered, thankfully, and the purple liquid pooled below. He shook his head.

“Whoops,” he said quietly.

Climbing the rack carefully, he tried several of the bottle tops until he came to one he thought might come free. This one was a clear bottle, but the insides looked pink instead of the dark, redish-purple the others had been. He looked over his shoulder once and, seeing not a soul, neither mouse nor human, started in on the cork.

He worked at it for hours, humming as he went. He clawed, bit, chipped away at the hard cork until it was nearly loose. Then he stood back and examined it. He looked down at the broken bottles and smelled his own purplish fur.

“I can’t make that mistake again,” he said, shaking his head.

“What mistake, Softy?”

Southy didn’t need to turn around to know who it was, but he did anyway. The massive, white mouse stood before him cackling proudly with his guffawing gaggle of henchmen surrounding him.

“Hello, Pooks,” Southy said.

“Whatcha doing here, Softy?”

“My name is Southy, Pooks,” he said. “But there are a lot of letters in my name and I’m sympathetic with how difficult it is to remember.”

Pooks thought about this for a second, then his frown grew frownier than before and his confused henchmen looked back and forth at each silently seeking a cue about what sort of behavior would be appropriate in this somewhat awkward situation. A few settled on nodding and saying, “Yea,” and others punched one fist onto their other palm and displayed faces that tried to convey to Southy that they meant his face was like the palm that was getting punched.

Southy nodded. He smiled. He clasped his hands behind his back and whistled the beginning of a happy, casual tune. Then he turned quickly back to the bottle and resumed his frantic tearing at the top. As he worked fast, the bottle shook, the contents sloshing around like a tumultuous sea. Pooks, likewise, was fairly frothing at this point.

“You stinking, little, purple-furred, human-lover!” Pooks shouted, rushing at Southy with his minions close behind. “You’re gonna get it!”

“I hope so,” Southy said quietly, straining at the cork.

Pooks was directly behind Southy now and raised his fist for a colossal punch. Pooks had punched a lot of mice in his time –it was kind of his thing– and he had an informal ranking system by which he distinguished the greatest of his fist-operated strikes from the least impressive. This one was, he could feel, even half-way through it, going to be the hardest punch of all his punch-happy life. So he closed his eyes and delivered, with a gleeful smile, the punch of all punches.

But Southy, having watched Pooks’ approach in a bottle’s reflection and having seen the build-up for this legendary punch, deftly sidestepped the bone-shattering blow at the last possible moment. Pooks’ thunderous right connected with the remains of the cork, blowing open the sloshing bottle of Champaign. Pink fluid blasted forth, spraying the white mouse and his screeching henchmen with such a blast as has never blasted the midnight marauding mice of any house in history.

Southy was tempted to just watch the blasted mice and try not to die from laughter. But he had a more urgent task. So Southy, after side-swiping the blow, mounted the bottle with surprising agility. There he made a tremendous effort to keep the exploding bottle from falling from its height and breaking into pieces, as had happened the previous three nights. A wild tumult followed where, rising and falling, Southy rode the bottle like a rodeo champion. It looked iffy for a moment, but he finally wrestled the bottle into a sputtering obedience.

It was over. Southy sat atop his spent steed –I mean the bottle– and looked out the small window at the top of the cellar. The moon was lovely, he thought, and he shook his head. Looking down, reflected in the moonlight, he saw a soaking, sagging, sorrowful bunch of mice. In their front lay a large, now-pink mouse, spluttering and, sobbing and, to Southy’s sympathetic amusement, shaking his head.

“Are you guys OK?” Southy said.

A few hours later, in the half-lit moments before dawn came to the valley, Southy shook hands with Pooks.

“Thanks, Pooks,” he said, his bulging satchel dangling behind him. “I couldn’t have done it without you guys.”

What he couldn’t have done was deposit the unbroken bottle on the bank of the river in the valley, some fifty yards from the house. After drying off, Pooks and his men had helped Southy finish his adventurous scheme by bringing the bottle all the way from the cellar to the river bank.

“It was nothing, Southy,” Pooks said. “We were pleased to do it.”

“Well, it means a lot to me,” Southy said, laying down the satchel with a sigh.

“I’m ever so sorry about how I treated you, friend Southy.”

“Don’t mention it,” Southy said, pointing to the bridge in the distance and the water beneath it. “It’s in our past, friend Pooks.”

They nodded together.

“All right, fellas,” Pooks said to his exhausted crew, “let’s let this fine mouse alone to do what he has planned.”

“Thank you,” Southy said, saluting the pink mouse as he began to trek back up to the house.

Southy turned to his bottle, then gazed up at the coming dawn. He sighed and shook his head, smiling wide. He moved toward the bottle.

“Wait,” he heard a kind voice from behind him. He turned and saw Nina parting the grass on the edge of the bank. “What are you doing, Southy?”

“Hi, Nina,” he said. He looked from her to the bottle, then out to the poking sliver of orange sun up river. He shook his head, smiling still. He dug inside his satchel, then drew out and unrolled a paper as tall as he was.

“What’s that?” Nina asked, her eyes curious and kind.

“It’s a poem,” he said. “About the moonlight.”

“Ah,” Nina said. They were both smiling.

Southy took the poem, rolled it neatly and slid it carefully into the empty bottle. He then drew out a cork from his satchel, plugged the bottle-top, and heaved on the bottle.

It rolled into the water, sunk briefly under, bobbed to the surface, then bounced down the river as dawn broke over the valley. Nina was silent and Southy was silent. They watched until they could see it no more, disappearing in the distance beneath the battered old bridge.

Finally, Nina spoke. “Who was the poem for?”

“Oh, anyone,” Southy said. “Anyone at all.”

- Make Believe Makes Believers - July 19, 2021

- The Archer’s Cup is Here - September 30, 2020

- It Is What It Is, But It Is Not What It Shall Be - March 30, 2020

- SW Shorts Get Shorter & Revisiting A Bear of a Dog Poem - January 8, 2016

- Red Bird’s Song - August 15, 2014

- Southy - April 4, 2014

My comment seems to have disappeared. Well, it basically said this: “This is awesome! I love it so much. Great work, Sam and Aedan.”

love this story! And can I just say, Aedan is one insanely talented 15-year-old boy – that illustration is brilliant.

Good story. A lot to glean. Nicely paced and humorous. The sudden friendship between Southy and Pooks (and Pooks’ henchmen) was strange and unconvincing to me, however. One moment they were ready to kill him, the next (albeit a few hours later) they were all friends. When Pooks said, “We were pleased to do it,” referring to helping Southy carry the bottle to the river, I was asking myself, “Why were they pleased to do it?” I felt this complete change wasn’t explored enough/accounted for in the story. “Was it the champagne?” I kept asking myself. Aside from that minor issue, I liked the story, especially the end, and will be happy to read it to my children, and I think the illustration is exceptional.