In some previous stage of my theological thinking, I conceived of the spiritual realm as an arena essentially separate from the materiality of daily life. More recently, influenced by the writings of N.T. Wright among others, I have come to realize the significance of the existing Creation as part of God’s eternal grand design.

The new creation, Wright stresses, is not something that is “up there” or “out there.” It commenced here on Earth with Christ’s resurrection and will be fulfilled, here on Earth, at his return. The kingdom of heaven is not so much “other” as “more”—an unseen that includes and extends beyond observable reality.

In tandem with this awareness has dawned a deeper understanding of why, at least for me, works of fantasy exert such a powerful draw. Whether transporting us to alternate worlds or introducing magical elements into this one (often to the skeptical, à la Eustace Scrubb), they treat the existence of Something More as a given. Maybe it only indicates that my theology needs to go to therapy, but I find it easier to believe the Bible when I’m reading Harry Potter.

Even if the books below do not precisely represent the Apostle Paul’s That Which Is Unseen, their discovery and perusal thrilled me not least because of their association with invisible realities. And besides, who among us has not itched to acquaint young readers with Narnia or Middle Earth at the earliest possible opportunity? If our four-year-olds aren’t quite ready to trudge through Mordor, there’s no reason we can’t prime their imaginations with hobbits.

The Literary Adventures of Washington Irving, American Storyteller, by Cheryl Harness (National Geographic, 2008, 48 pp., ages 7–10)

Washington Irving’s pursuits cut a broad swath across 19th-century American history. The inclusion of this title may have more to do with my delight in the Harness’s work than with Irving’s qualifications as a fantasist. He did give us The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle. But he also served as a diplomatist, businessman, lawyer, explorer, newspaperman, and biographer (chronicling the lives of Mohammed, Christopher Columbus, and George Washington—the latter in five volumes).

Harness paints an appealing portrait of an adventuresome and amiable man with a fascination for the world at large as well as the country of his birth. Her detailed drawings merit close attention and could almost carry the story on their own. On investigation I discovered Harness has written a number of other brilliantly conceived and illustrated histories, which I intend to retrieve from the library at the earliest possible opportunity.

She Made a Monster, by Linn Fulton, ill. Felicita Sala (Knopf , 2018, 40 pp., ages 4–8)

British author Mary Shelley numbered among the friends and admirers of the near-contemporary Washington Irving (see above). Fulton’s succinct account of the creation of Frankenstein capitalizes on both scientific history and the thrill of a ghost story. She cites 19th-century experiments with electricity, such as physician Luigi Galvani’s making a dead frog kick and another scientist’s making a corpse move. Fulton imagines how Mary Shelley’s imagination might have run—and perhaps run away—with these ideas. Sala’s illustrations include rudimentary images of ghouls and witches without growing excessively alarming.

The text incorporates Shelley’s personal history—her feminist mother, her friendship and eventual marriage to poet Percy Shelley, and the ghost story challenge that inspired the groundbreaking novel. Fulton also acknowledges the ethical themes sometimes obscured by later renderings of Shelley’s masterpiece. Some of these are highly relevant to today’s conversations about AI. What, for example, constitutes responsible use of science and technology? Is the ability to do something sufficient justification for doing it?

One Fun Day with Lewis Carroll, by Kathleen Krull, ill. Júlia Sardà (Clarion, 2018, 32 pp., ages 6–9)

Krull’s whimsical text employs many of the colorful terms coined or adapted by Alice in Wonderland author Charles Dodgson.A minor complaint is that throughout this account of Dodgson’s early life and the writing of Alice the famed author is referred to as “Lewis.” In reality, he didn’t assume what was to become his pen name until he was in his 20s.

Dodgson’s lexical creations appear in a glossary at the back. Sardà’s colorful illustrations, bursting with life and energy, are well suited to the haphazard world of Wonderland. I gleaned at least two new facts from this volume: Dodgson gained his affinity for children from being elder brother to ten siblings, and, in addition to his flights of fancy, he published weighty works on mathematics.

Note: A more in-depth and unfortunately out-of-print resource for older readers is The Other Alice: The Story of Alice Liddell and Alice in Wonderland, by Christina Bjork, ill. Inga Karin-Eriksson, trans. Joan Sandin (Rabén & Sjögren, 1993, 93 pp., ages 8 & up). Lovely illustrations (B&W as well as color) and two- to four-page sections present an engaging, fictionalized account of Dodgson’s friendship with Alice and her family. Interspersed are segments on topics such as science and culture in Victorian England, Dodgson’s personal history, and 19th-century games and puzzles.

The Road to Oz: Twists, Turns, Bumps and Triumphs in the Life of L. Frank Baum, by Kathleen Krull, ill. Kevin Hawkes (Knopf, 2008, 48 pp., ages 4–10)

Baum’s is the sort of story that encourages struggling writers: long-delayed success after repeated failures, rejections, and mis-directions. Not all of Baum’s false starts involved literature. By the time The Wizard of Oz staggered Baum’s wife with its surprise success, Baum had tried his luck as an actor, chicken breeder, shopkeeper, and traveling salesman (of fine china). He had penned forgettable books aplenty (though you can purchase The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors online)before realizing he should offer to a wider audience the fantastic stories with which he entertained his children and the neighbors.

The lifelong success Krull does attribute to Baum is fatherhood. She credits him with devoted attention to his four young sons and with the assertion that “If I had my way, I would always have a young child in the house.” Of the authors listed here, it is interesting to note that Irving and Dodgson never married, but as with Baum, Tolkien’s children served as powerful inspiration for his literary ventures. Lewis, who never had children of his own, carried on a lively correspondence with his juvenile readers and cared for his two stepsons after the death of their mother.

Krull’s afterword reveals that, though Baum never escaped financial troubles altogether, a musical based on Oz met with great success during his lifetime. He went on to produce another thirteen books in the series (and a total of more than seventy children’s books). As with Irving, one might conclude that a life characterized by varied pursuits lends itself to productive creativity.

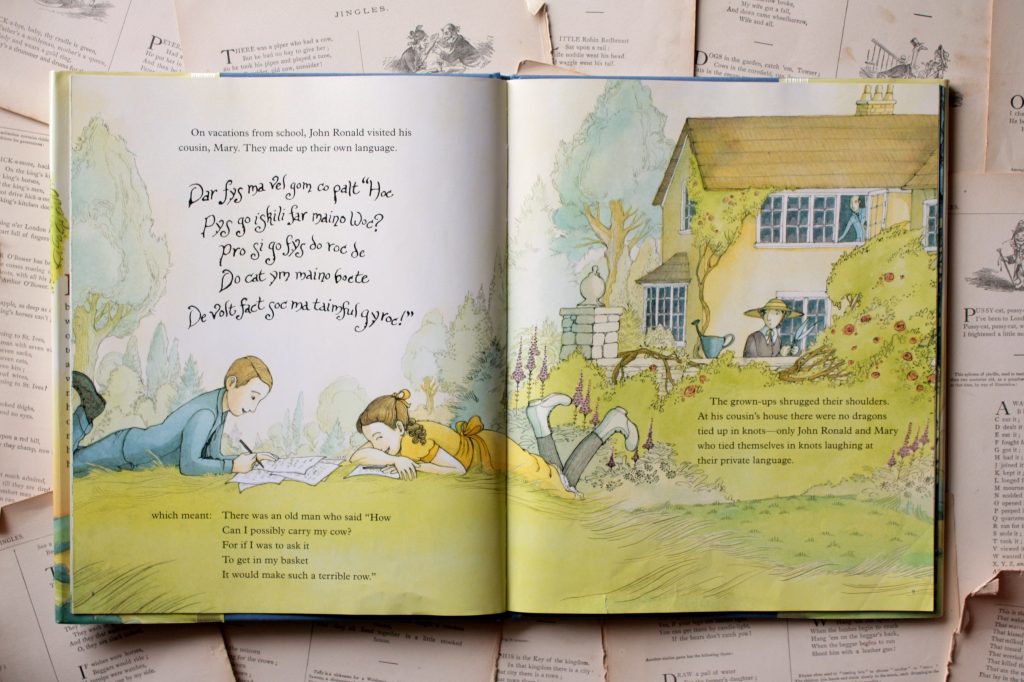

John Ronald’s Dragons, by Caroline McAlister, ill. Eliza Wheeler (Roaring Brook Press, 2017, 48 pp., ages 4–8).

It was the discovery of this book, along with Finding Narnia (below), thatinspired this collection of reviews. As a lover of both Tolkien and picture book biographies, I only wonder how this one escaped my attention for so long. The cover drew me immediately, with its fanciful depiction of an imagined (as opposed to real, of course) dragon against idyllic English countryside.

And indeed, the book suggests that this sums up Tolkien’s life. He loved England and, aside from (perhaps because of?) his Great War experience, rarely ventured far from the familiar confines of home. And yet dragons held the same awful and fascinating enchantment for him that they have exercised over imaginations worldwide for millennia.

Of course there is more to Tolkien than dragons and a love for rural life, and even this brief history touches on some of it—the loss of his mother in childhood, his stuttering romance with Edith, and his camaraderie with fellow scholars, first at boarding school and then at Oxford. A one-page author’s postscript fills in a few details, and the illustrator’s note elucidates her clever incorporation of Tolkien trivia, like his favorite childhood books and lone memory of his father.

Finding Narnia: The Story of C.S. Lewis and His Brother, Caroline McAlister, ill. Jessica Lanan(Macmillan, 2019, 48 pages, ages 4–8)

While this book supplies the expected biographical information leading up to Clive Staples (Jack) Lewis’s penning of the Narnia stories, I especially appreciate the homage paid to the friendship between the author and his older brother, Warren (Warnie). The text highlights the complementary nature of their differing personalities. While Jack inhabited the world of imagination, Warnie reveled in detailed maps, diagrams of ships, and railroads traversing the real world.

Both primary text and back matter introduced me to hitherto unknown facts. Like Professor Kirk in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the brothers harbored war refugees from London during WWII. I was also unaware that Warnie, who outlived Lewis by ten years, published seven books of his own on French history. A precious few copies of his Brothers and Friends: The Diaries of Major Warren Hamilton Lewis are available from online sellers. If I ever run across one for less than $50 I will snatch it up. Incidentally, our public library has a copy of Boxen: Childhood Chronicles before Narnia (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985), also readily available online. Not especially engaging as literature, it nevertheless offers an intriguing glimpse into Warnie and Jack’s early creations. Perhaps only coincidentally, Lanan’s watercolor style in Finding Narnia is reminiscent of the Boxen illustrations.

Featured image by Little Book, Big Story

- Birthday with the Bard - April 10, 2024

- What History Is Made Of - March 25, 2024

- Books for Black History Month, pt. 2 - February 19, 2024

Leave a Reply