Hispanic Heritage Month came to my attention only recently, but the annual commemoration originated in 1968. Initially a week in duration, it was extended to one month in 1988. The event begins mid-month because it was on September 15, 1821, that Costa Rica, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Guatemala declared their independence from Spain.

I spent my first four years of life in California and Texas, where Spanish presence dates to the 1600s. Like most preschoolers, I was alert to little outside my immediate family, which happens to have northern European roots. By middle school my parents and I were firmly planted in Oregon. If a Latino presence existed in our small town, I remained ignorant of it. Nevertheless my parents, firmly convinced of the value of multiculturalism, enrolled us in a Saturday morning Spanish class at the local community college.

After high school I left the area for more than a decade, returning for grad school and remaining to start my own family. When my daughter started first grade—in the building that had previously been my middle school—she attended Spanish literacy classes alongside the children of the large Latino population that had grown up in my absence. The experience introduced us to a number of the books included here.

I have selected titles that feature language in part because of these fond associations but also because language is endemic to culture and identity. English is enriched by countless Spanish loan words, integrated with varying degrees of visibility. Terms like “ranch,” “breeze,” and “patio” (from rancho, brisa, and patio)have been so thoroughly anglicized that their Spanish origins often go unnoticed. Other words, like “burrito,” generally (though not always) point to items widely recognized as Latin-American. Although many of these books were written for younger children, older readers learning Spanish can enjoy and benefit from them as well.

Buenas Noches, Gorila, by Peggy Rathmann (G.P. Putnam, 2004, 34 pp., ages 1–3)

I wavered over whether to include the two Rathmann titles in this list, as they are translations from English and represent nothing distinctly Latino. However, as bedtime books and vocabulary builders they are irresistible. Here, a zookeeper makes his rounds at night, bidding each of his charges buenas noches in turn. Only after he and his wife retire to bed and turn out the lights do they realize all the animals have followed him home and crowded into the bedroom.

10 Minutos y a la Cama, by Peggy Rathmann (G.P. Putnam, 2005, 16 pp., ages 1–3)

As with the previous title, a comic conceit conveyed solely through illustrations complements spare text. In this case a company of hamsters begins showing up at the protagonist’s door just as his father pronounces ten minutes to bedtime. While dad counts down the minutes (echoed by the head hamster), the boy goes through his bedtime routine. Meanwhile, the frolicking hamsters keep streaming in. Youngsters studying the detailed pictures will hardly realize they’re learning to count (backwards). Parents who have worn out English phrases directing their children to bed might try switching to Spanish: “A la cama!”

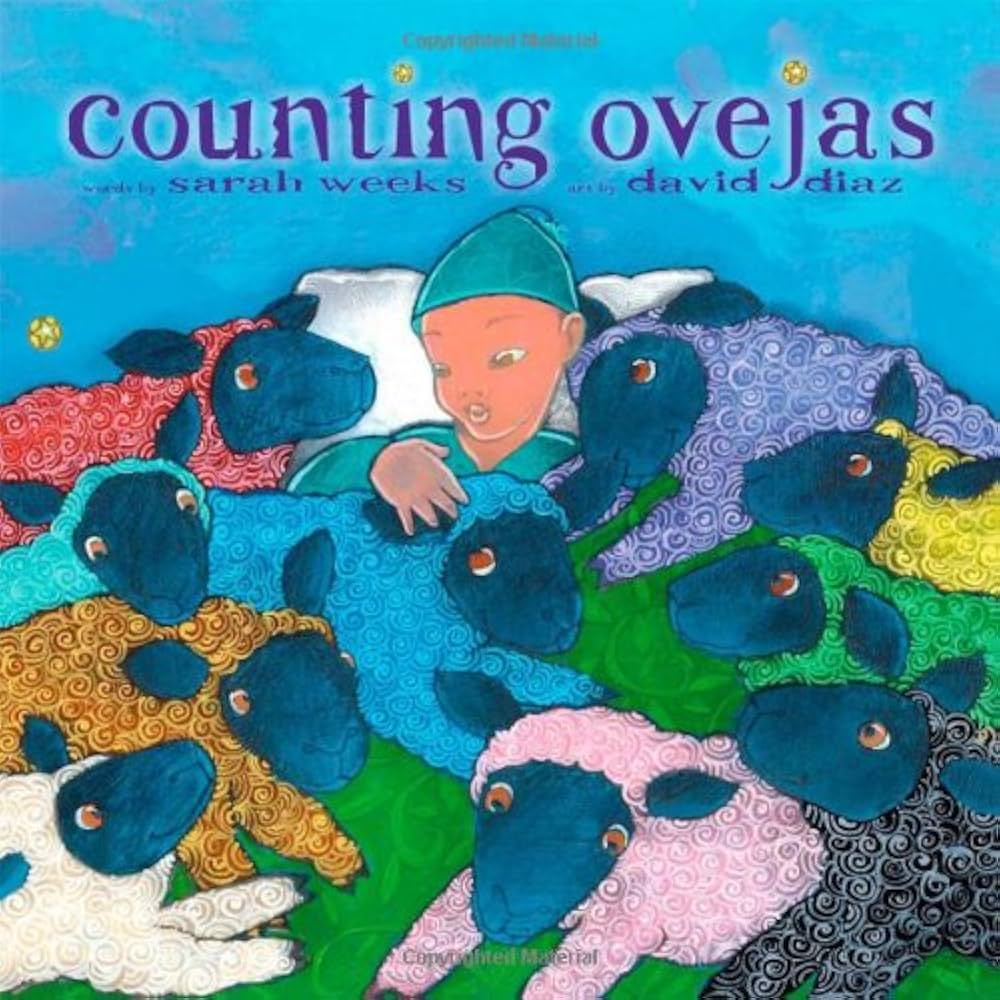

Counting Ovejas, by Sarah Weeks, ill. David Diaz (Atheneum, 2006, 40 pp., ages 3–8)

Here, too, bedtime offers occasion to practice numbers, as well as colors. The text is bilingual and, for readers lacking confidence in their language proficiency, the Spanish is glossed with phonetic pronunciation underneath. The would-be sleeper of the story bids goodbye to progressively larger groups of sheep, trundling them away by more and more creative means as their numbers increase. Sweet, playful, and potentially calming, if your youngsters aren’t excessively entertained.

Salsa Lullaby, by Jen Arena, ill. Erika Meza (Knopf, 2019, 32 pp., ages 2–7)

Lilting rhymed text accompanies lively depictions of a mother and father dancing their baby into bed. Each repetition of the refrain incorporates a different Spanish word, i.e. baila, canta, mira (dance, sing, look). Another charming, out-of-print but still available lullaby book in verse is Te Amo Bebé, Little One, by Lisa Wheeler, ill. Maribel Suárez (Little, Brown, 2004, 32 pp., ages 2–4).

Marta Big and Small, by Jen Arena, ill. Angela Dominguez (Roaring Brook, 2016, 32 pp., ages 4–7)

Simple text and illustrations introduce adjectives in pairs of opposites. Marta is big or small, fast or slow, quiet or loud, depending on what she’s compared to. But always she is clever, very clever. An appropriately clever twist at the end adds to the fun. As with Buenas Noches, Gorila, readers of Marta will learn and practice Spanish words for various animals.

Alma and How She Got Her Name, by Juana Martinez-Neal (Candlewick, 2018, 32 pp., ages 3–8)

Alma Sofia Esperanza José Pura Candela dislikes her very long name. Until her father recounts all the ancestors who have bequeathed their names to her and the affinities Alma shares with them. Lovely illustrations feature muted colors (with the exception of Alma’s signature red-and-white striped pants) and flowing lines. In addition to exploring Latino culture, the story touches on the relationship between individual identity and family history. Readers like me with a scant two given names might find themselves feeling short-changed.

Quiero Ayudar!—Let Me Help!, by Alma Flor Ada, ill. Angela Domínguez (Children’s Book Press, 2010, 32 pp., ages 5–8)

A fanciful account of a parrot thwarted in his efforts to help his family celebrate fiesta in San Antonio. The text is bilingual, and the story incorporates cultural elements like folklorico dancing, mariachi bands, and the making of tamales and pan dulce.

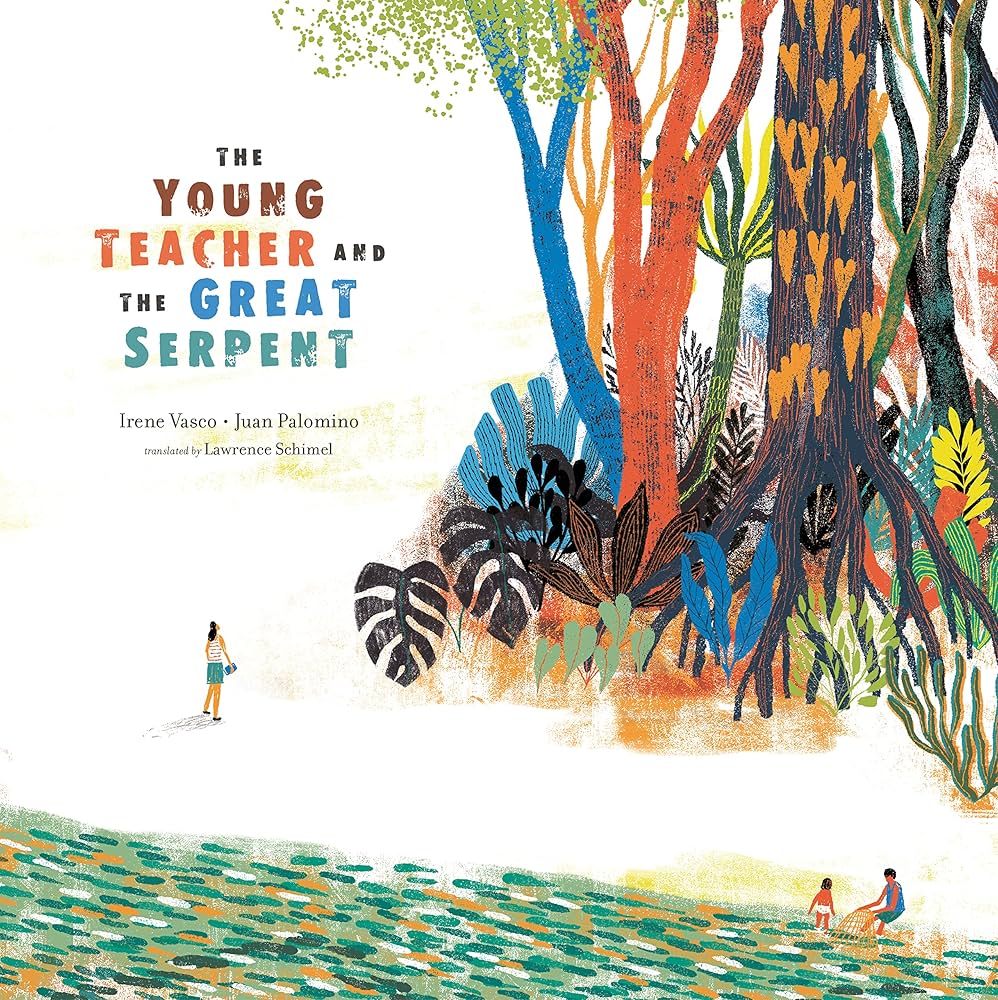

The Young Teacher and the Great Serpent, by Irene Vasco, ill. Juan Palomino, trans. Lawrence Schimel (Eerdmans, 2023, 40 pp., ages 5–9)

Vasco describes the long jungle journey of a young teacher intent on imparting science, math, and the wonders of books to eager new pupils. Initially skeptical of myth and legend, she soon discovers the value of folkways and oral tradition. Possibly inspired by the author’s own experiences teaching in remote areas of Colombia, The Young Teacher offers a glimpse of communities where Spanish comes second to indigenous languages.

Note: Among the wealth of resources available for further research is this feature by the American Writers Museum in Washington, DC, on Hispanic writers throughout history: AWM National Hispanic American Heritage Month.

- Birthday with the Bard - April 10, 2024

- What History Is Made Of - March 25, 2024

- Books for Black History Month, pt. 2 - February 19, 2024

Leave a Reply